Press conferences are curious events. Conferences are called by organizations, or individuals, when they have something they want made public.

A press conference is only as successful as what the members of the media are willing to accommodate. If the press isn’t interested in the subject, the public won’t know anything about it. Press conferences cost nothing, while other means of communication can become exorbitant.

The key to a successful press conference is being able to persuade journalists that their topic constitutes news. Convincing the media is based on what is referred to as a common “news value.” It is what brings members of the media together at any event and answers the question, what is news.

Certain individuals and organizations are assured coverage. The President, Governors, Mayors, and law enforcement, all seem to get coverage when requested. This is March 4, 1996, news conference took place on the front steps of Albuquerque's Law Enforcement Center to brief the media on details of the Hollywood Video store murders of five victims.

Certain individuals and organizations are assured coverage. The President, Governors, Mayors, and law enforcement, all seem to get coverage when requested. This is March 4, 1996, news conference took place on the front steps of Albuquerque's Law Enforcement Center to brief the media on details of the Hollywood Video store murders of five victims.Media outlets are inundated daily with what are termed: “news releases,” “press releases,” or “media advisories.” There is an industry of press agents, public information officers and communications and marketing individuals, whose sole purpose is to try to get out a free message to the public through the media. Setting the agenda for a press conference is crucial to the “right message” getting reported upon and not allowing the media to redirect the purpose.

On occasion, a press conference may be an ad-hoc event. This 2001 end of a high-speed pursuit, by New Mexico State Police that ended when a stolen vehicle ran over spike belts and crashed into an Interstate Highway 25 median barrier. The ranking supervisor answered questions for local television cameras.

On occasion, a press conference may be an ad-hoc event. This 2001 end of a high-speed pursuit, by New Mexico State Police that ended when a stolen vehicle ran over spike belts and crashed into an Interstate Highway 25 median barrier. The ranking supervisor answered questions for local television cameras.Often the agenda of those calling a press conference is not what the media reports.

During political seasons, press conferences appear early during campaigns with candidates wishing to get their name and initial issues before the public. Over the course of the campaign, stated issues become repeated, “talking points.” Open press conferences slowly become rare events. Political media consultants, press secretaries and communications directors want to control the message at a certain point -- that point is when a question is asked that causes problems for the campaign or the candidate. Such a problem is not always the same thing for the candidate and the campaign.

How a campaign manages the candidate’s answer is often more important than what the question was.

There were two fine examples of that, in which both New Mexico Congressional District One candidates held press conferences and the Communications Directors cut off the meeting with the press by announcing, ”one more question.” Each took an additional question after the, “one more.”

In Republican Bernalillo County Sheriff Darren White’s case, he announced his return to the campaign trail after injuring his back and spending a week in the hospital, above. It was possibly his second most important press conference; the first was his initial announcement to run, below. He was genuine and the topic, his health being good enough to continue to run, was important.

In Republican Bernalillo County Sheriff Darren White’s case, he announced his return to the campaign trail after injuring his back and spending a week in the hospital, above. It was possibly his second most important press conference; the first was his initial announcement to run, below. He was genuine and the topic, his health being good enough to continue to run, was important. After the “one more,” I asked a question that was not contained in all the previous questions -- was he possibly facing surgery? He gave a good response; it lacked spin. Though he was still in obvious pain, he pushed forward. It might have been a turning point in his campaign, because his momentum seemed to wane.

After the “one more,” I asked a question that was not contained in all the previous questions -- was he possibly facing surgery? He gave a good response; it lacked spin. Though he was still in obvious pain, he pushed forward. It might have been a turning point in his campaign, because his momentum seemed to wane. Here's a Sept. 3, 2008, "press conference" with only eight media representatives present for a hastily called gathering with Democrat and now newly elected Representative Martin Heinrich, meeting with House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland.

Here's a Sept. 3, 2008, "press conference" with only eight media representatives present for a hastily called gathering with Democrat and now newly elected Representative Martin Heinrich, meeting with House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland.Heinrich arrived 45-minutes late keeping the second-highest ranking member of Congress and the press waiting. “Sorry I'm late,” he said, …don't want to get stopped by a deputy; in a poke at his rival’s occupation.

After giving brief statements about alternative energy at Sandia Labs, Hoyer and Heinrich answered only two questions before the “thank you,” was called, as the last question. KKOB News Radio’s Political Chief Reporter Peter St. Cyr protested and continued to press Heinrich.

St. Cyr, left would be characterized by NMFBIHOP Blogger and New Mexico Independent Reporter Matthew Reichbach, as “pushy” when he asked a third question.

St. Cyr, left would be characterized by NMFBIHOP Blogger and New Mexico Independent Reporter Matthew Reichbach, as “pushy” when he asked a third question.It appears the Heinrich campaign removed St. Cyr from their press release list. A review of St. Cyr’s site reveals a lack of Heinrich’s campaign generated media advisories.

Heinrich has always been open with me, but his campaign staff ran interference for him repeatedly, as seen here when I got him to talk with Joe Monahan on the KANW AM election night coverage after the 2008 primary about his victory. I ignored them and always made direct contact. Hopefully, the new Congressman will recognize the potential problem he faces in acquiring good access and reigns in or directs his communications staff to be open and cooperative with the press.

Heinrich has always been open with me, but his campaign staff ran interference for him repeatedly, as seen here when I got him to talk with Joe Monahan on the KANW AM election night coverage after the 2008 primary about his victory. I ignored them and always made direct contact. Hopefully, the new Congressman will recognize the potential problem he faces in acquiring good access and reigns in or directs his communications staff to be open and cooperative with the press.St. Cyr and KKOB remain open to the freshman Congressman and hopefully his new staff will avail themselves of the most powerful station, at 50,000 watts, in the Congressional district; one of only two local radio stations with actual news staffs.

The Heinrich camp might argue that they were running late at Sandia and they had to visit the Solar tower and other research facilities that were closed to the media. However, Heinrich called the press conference, which should mean a conference with the press.

So what’s wrong with this picture?

This is a press conference held at the Western New Mexico Correctional Facility near Grants, hosted by Warden Anthony Romero, below left, April 24, 2008. The purpose of the conference was to discuss a cutting edge treatment program that the University of New Mexico Psychology Department’s Associate Professor Kent A. Kiehl, right, is conducting. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic tool, Kiehl is attempting to determine the best treatment for convicts whose substance abuse may have led them to prison.

This is a press conference held at the Western New Mexico Correctional Facility near Grants, hosted by Warden Anthony Romero, below left, April 24, 2008. The purpose of the conference was to discuss a cutting edge treatment program that the University of New Mexico Psychology Department’s Associate Professor Kent A. Kiehl, right, is conducting. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic tool, Kiehl is attempting to determine the best treatment for convicts whose substance abuse may have led them to prison. Kiehl, who was lured to UNM from Yale University School of Medicine, is using grants from: the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health through UNM’s Mind Research Network. His research is addressing one of the most significant underlying contributors to crime – substance abuse.

Kiehl, who was lured to UNM from Yale University School of Medicine, is using grants from: the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health through UNM’s Mind Research Network. His research is addressing one of the most significant underlying contributors to crime – substance abuse.

During former Governor Gary Johnson’s second term, he tried to open a discussion about treating convicts for substance abuse before returning them to society. Johnson’s ideas were part of a wider dialogue about drugs and the criminal justice system’s response to them.

During former Governor Gary Johnson’s second term, he tried to open a discussion about treating convicts for substance abuse before returning them to society. Johnson’s ideas were part of a wider dialogue about drugs and the criminal justice system’s response to them.Johnson’s proposals met wide spread derision, especially amongst the specialized anti narcotics law enforcement sector and political factions who have staked their reputations and fortunes on the “War on Drugs.” These groups advocate a punishment only approach to the problem.

The problem is no small issue:

The problem is no small issue:The United States now incarcerates a larger percentage of its population than any other country in the world.

The annual cost for incarceration is $1.3 trillion, according to Kiehl.

A figure that has been bouncing around for years and seems undisputed is that well over 80 percent of all those currently incarcerated will be returned to the community.

Further, well over 80 percent of all those currently incarcerated were under the influence of a substance at the time they committed the crime for which they are in prison.

There is a history of very little effort within the criminal justice system to treat the substance abuser except through “cold turkey” abstinence as a result of incarceration.

“The inmates lived in complete isolation, with a Bible their only possession, and chores like shoemaking and weaving to occupy their time,” according to the Smithsonian Institutes history of the penal philosophy of America’s first prison, Eastern State Penitentiary near Philadelphia, built in 1822.

Many still view such a fundamental philosophy as an adequate form of punishment.

This philosophy doesn't work; drugs are prevalent in the prison. This is part of a display exhibiting drug paraphernalia confiscated from inmates at the facility.

This philosophy doesn't work; drugs are prevalent in the prison. This is part of a display exhibiting drug paraphernalia confiscated from inmates at the facility.

Kiehl lists his primary area of faculty work as “cognition, brain and behavior.” He works at MRN, which is housed in the Pete and Nancy Domenici Hall, above, on UNM’s North Campus.

Kiehl lists his primary area of faculty work as “cognition, brain and behavior.” He works at MRN, which is housed in the Pete and Nancy Domenici Hall, above, on UNM’s North Campus. Retiring U.S. Senator Pete Domenici, with his wife Nancy, has worked tirelessly on federal funding for mental health research. Part of his reasoning is because of his fourth child; his daughter, Clare, 46 who struggles with mental illness.

Retiring U.S. Senator Pete Domenici, with his wife Nancy, has worked tirelessly on federal funding for mental health research. Part of his reasoning is because of his fourth child; his daughter, Clare, 46 who struggles with mental illness. Clare, middle, with her father, right as he talked to Sam Donaldson who was the master of ceremonies for "Here's to Pete: A Celebration of Senator Domenici's Service to New Mexico and the Nation," sponsored by New Mexico First on June 28, 2008.

Clare, middle, with her father, right as he talked to Sam Donaldson who was the master of ceremonies for "Here's to Pete: A Celebration of Senator Domenici's Service to New Mexico and the Nation," sponsored by New Mexico First on June 28, 2008.With Senators Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), Mike Enzi (R-Wyo.) and Chris Dodd (D-Conn.), Domenici passed the mental health parity agreement just weeks before announcing his retirement, Oct. 4, 2008. Domenici cited his own diagnose of frontotemporal lobar degenration a rare form of dementia.

The press conference included a tour of “H” wing; the treatment pod, seven “slams” deep. A slam is the way of knowing how deep you are in a prison. The slam is the closing of a locked gate behind you; the higher the number, the deeper you are. You couldn’t get much deeper at Western. It is only by the grace of your host that you will return to the free society.

The press conference included a tour of “H” wing; the treatment pod, seven “slams” deep. A slam is the way of knowing how deep you are in a prison. The slam is the closing of a locked gate behind you; the higher the number, the deeper you are. You couldn’t get much deeper at Western. It is only by the grace of your host that you will return to the free society. There were strict rules imposed on this press conference for security reasons by the Department of Corrections, through Deputy Warden of Administration Deanna Hoisington, left, who doubles as media relations spokesperson at the facility, and Captain Frank Chavez. Because the testing falls under medical research, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, comes into play. We were not allowed to specifically ask questions of the inmates because they were also patients, whose privacy is protected by HIPAA.

There were strict rules imposed on this press conference for security reasons by the Department of Corrections, through Deputy Warden of Administration Deanna Hoisington, left, who doubles as media relations spokesperson at the facility, and Captain Frank Chavez. Because the testing falls under medical research, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, comes into play. We were not allowed to specifically ask questions of the inmates because they were also patients, whose privacy is protected by HIPAA.I was told that I had to have permission from any inmate before photographing them, and the staff had to obtain a written release.

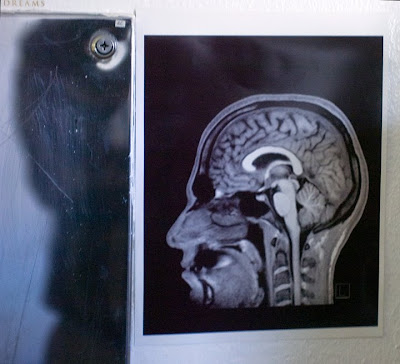

It all sounded confusing and a potential major barrier to reporting, but it wasn’t. Upon entering “H” pod, the inmates were milling around and a quick look in the first cell revealed a MRI film on the wall. I asked the resident of the cell if I might take a picture and he seemed happy to let me.

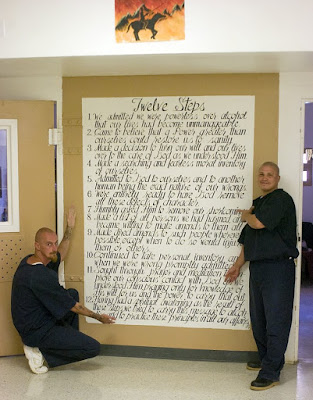

It all sounded confusing and a potential major barrier to reporting, but it wasn’t. Upon entering “H” pod, the inmates were milling around and a quick look in the first cell revealed a MRI film on the wall. I asked the resident of the cell if I might take a picture and he seemed happy to let me.“H” pod is a treatment unit and has inmate paintings on the walls including a 12-step program to recovery.

Inmates Christopher Hahs, left, in prison for possession of a firearm by a felon and Rocky Ruiz, right, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, caught my attention by pointing out the 12–step mural.

Inmates Christopher Hahs, left, in prison for possession of a firearm by a felon and Rocky Ruiz, right, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, caught my attention by pointing out the 12–step mural. Hahs' substance of choice was methamphetamine and said that he hoped his participation in treatment would help him reintegrate into society.

Hahs' substance of choice was methamphetamine and said that he hoped his participation in treatment would help him reintegrate into society.Kiehl walked us through hallways where his student interns were interviewing inmates. He led us to a mobile self-contained MRI unit housed in an over-the-road trailer within an inner perimeter razor wire topped chain-link fence under the 70-foot guard tower.

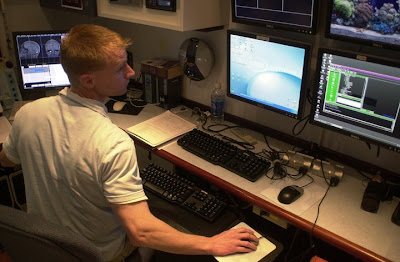

Inside, a session was in progress. Chief Technician Keith Harenski was running a program and closely monitored a bank of computer screens, paying particular attention to data as it appeared on a specific screen. The process displayed a series of words to the inmate who lay inside the MRI’s tube with its spinning magnet and measuring equipment.

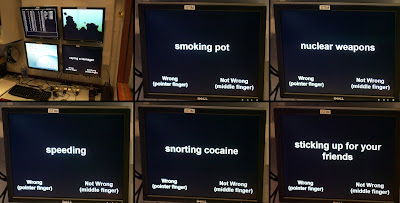

Inside, a session was in progress. Chief Technician Keith Harenski was running a program and closely monitored a bank of computer screens, paying particular attention to data as it appeared on a specific screen. The process displayed a series of words to the inmate who lay inside the MRI’s tube with its spinning magnet and measuring equipment. The words and phrases were to be rated morally by the inmate by moving his fingers on a recording device. Part of the test was to record how long it took to decide whether the word was “Wrong” or “Not Wrong.”

The words and phrases were to be rated morally by the inmate by moving his fingers on a recording device. Part of the test was to record how long it took to decide whether the word was “Wrong” or “Not Wrong.”

This is The New Yorker magazine’s Reporter at Large John Seabrook. In the Nov. 10, 2008 issue of the magazine, he writes an article as “A Reporter At Large” entitled “Suffering Souls: The search for the roots of psychopathy,” about psychopaths and research being done in New Mexico.

This is The New Yorker magazine’s Reporter at Large John Seabrook. In the Nov. 10, 2008 issue of the magazine, he writes an article as “A Reporter At Large” entitled “Suffering Souls: The search for the roots of psychopathy,” about psychopaths and research being done in New Mexico.Seabrook came away from the press conference at Western Correctional with an entirely different take on what I found to be significant.

As an aside, Kiehl mentioned that the MRI could be used to try to identify psychopaths.

Kiehl told the story of having grown up in Tacoma, Washington, where his father had been the news editor for the News Tribune. Serial killer Ted Bundy had lived down the street and nobody could believe he was a psychopath until he was convicted.

Psychopaths are probably more fascinating than drug using criminals.

However, by comparison, psychopaths represent a mere fraction of the inmates, crimes and killings, as compared to the substance abusers in prison.

Seabrook writes an 8,300-word history of psychopathy and the use of MRI in New Mexico.

Keihl’s MRI research is receiving a great deal of interest. Following are links to other media presentations on the MRI’s treatment potential.

Keihl’s MRI research is receiving a great deal of interest. Following are links to other media presentations on the MRI’s treatment potential.KOAT TV on November 14, 2008 ran a story entitled, “Can MRI’s Show Criminals.”

Albuquerque Journal Staff Writer Jackie Jadrnak wrote on November 20, 2006, an article entitled, “Researchers Studying Minds of Psychopaths.”

Albuquerque Journal Assistant Business Editor Autumn Gray wrote on October 05, 2008, an article entitled, “Local Neuro-Imaging Research Has Potential To Save Taxpayer Money, Cut Social Costs.”

Greg Miller wrote an article for the September 5, 2008 issue of Science Magazine entitled, “Investigating the Psychopathic Mind.”

My Take

My TakeThough Keihl believes that up to a third of inmates may fit the psychotic models, it is clear that substance abuse and addiction pose a much higher threat and problem for society at large.

It seems that the treatment possibilities are better proven for the drug and alcohol dependent inmates than the psychotic. Seabrook points out that there is not even an agreed upon definition within the mental health community, as to what constitutes a psychotic.

Though the research is compelling, if getting ahead of the drug treatment is more effective, it has a greater potential of reducing crime. For as bad and violent psychotics can be, they don’t pose the threat that abusers do statistically.

I never expected to be able to illustrate a New Yorker article with a humble photo essay of a story that wasn’t going anywhere, of a remote desert prison, but here it is.

I never expected to be able to illustrate a New Yorker article with a humble photo essay of a story that wasn’t going anywhere, of a remote desert prison, but here it is.

1 comment:

Cool, I am in your first two pictures. What are the odds?

Cheers, Mi3ke

Post a Comment