Note: I have had an interest in labor issues, particularly those of the City of Albuquerque. Over the past couple of months city employee organizations have experienced and been confronted by fundamental changes in the application of the Labor-Management Relations Ordinance. I write from the perspective of having been a union leader and a graduate student. I hold a master’s degree in public administration with a specialization in public personnel management.

Note: I have had an interest in labor issues, particularly those of the City of Albuquerque. Over the past couple of months city employee organizations have experienced and been confronted by fundamental changes in the application of the Labor-Management Relations Ordinance. I write from the perspective of having been a union leader and a graduate student. I hold a master’s degree in public administration with a specialization in public personnel management.Since retirement, I have occasionally been consulted about the labor history in Albuquerque government. I have strong opinions about large national labor unions and how they use their economic power for political purposes. Those opinions are not always good. Amongst Albuquerque’s government employee unions there are seven unions: four are now represented by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees: Blue Collar, Clerical, Security, and Management. The Transit Department drivers now seem destined to join AFSCME. The other unions are Police and Fire.

A quick review: Albuquerque adopted a Labor-Management Relations Ordinance in the early 1970s after a wildcat strike by blue-collar workers.

A quick review: Albuquerque adopted a Labor-Management Relations Ordinance in the early 1970s after a wildcat strike by blue-collar workers. Albuquerque Police Department Sergeant Robert Lavendowski and Officer Phil Edwards load .12 gauge shotguns in preparation for a confrontation with city blue collar refuse collectors who had staged a wildcat strike at the city’s Pino yards September 9, 1970. This overwhelming show of deadly force kept the workers calm.

Albuquerque Police Department Sergeant Robert Lavendowski and Officer Phil Edwards load .12 gauge shotguns in preparation for a confrontation with city blue collar refuse collectors who had staged a wildcat strike at the city’s Pino yards September 9, 1970. This overwhelming show of deadly force kept the workers calm.

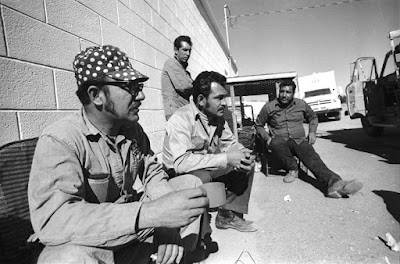

Union Leader Henry Campos, at left, president of the city blue-collar workers union, talks with other city workers during breaks. While a strong advocate of improved wages and working conditions for his men, Campos desires to avoid, if possible, serious confrontations with the city. “A strike is no good for anybody.”This photograph and caption appear as they did on the Feb 18, 1971, Albuquerque News front page, under the headline, “City and Union Coming to Showdown.”

The new labor ordinance allowed workers to form into unions that would collectively bargain. The City Commission, at that point, adopted a law that was very strict about how workers could and would select their exclusive representative.

The ordinance rightly starts at the beginning, with the idea that no union exists and it delineates a procedure for allowing workers to choose their representatives.

The process is modeled on federal law, the National Labor Relations Act which established the National Labor Relations Board to administer the law in the private sector. The NLRA and its NLRB do not apply to the federal, state, local governments or other political subdivision under the theory of federalism. Governments are permitted to chose to enter into collective bargaining or not.

After an exclusive representative is established, Albuquerque’s ordinance anticipates what might happen should workers choose a different organization to represent them. The ordinance requires the workers to vote for decertification of their current union first.

As long as an organization appropriately recognized as the exclusive bargaining agent of city employees is in place, no other organization or union may directly attack them or try to take them over.

The ordinance presupposes that there may only be one of two conditions: there is an exclusive bargaining agent, or there is no exclusive bargaining agent.

The provision for changing the exclusive bargaining representative is through decertification. There are three methods of decertification:

The mayor shall decertify a bargaining agent should a union support or lead a strike, which is deemed a fatal illegal act.

The mayor shall decertify a bargaining agent should a union support or lead a strike, which is deemed a fatal illegal act. The City may determine that an agent is not representing a majority of a bargaining unit, at which time the mayor shall decertify the bargaining agent.

The City may determine that an agent is not representing a majority of a bargaining unit, at which time the mayor shall decertify the bargaining agent. Employees of a bargaining unit may call for an election to decertify.

Employees of a bargaining unit may call for an election to decertify.The choices on a ballot in a decertification election shall be the incumbent exclusive bargaining representative and no representation.Decertification is a double-edged sword, because once decertification election is held,

If a majority of the city employees in the bargaining unit vote in favor of decertification of an employee organization, the Mayor shall decertify that employee organization as the exclusive bargaining representative for the bargaining unit.After decertification by the mayor, there is a mandatory one-year moratorium in collective bargaining for those affected employees before workers are allowed to again select a bargaining representative.

At the end of the year, the process for establishing an exclusive bargaining agent is the same as the original process for determining or electing an agent. It is as if there never was a bargaining agent.

The city, however, has refused to follow its own ordinance and has not objected to the Labor Board deciding that one union may attack another without going through the decertification process.

It seems that the barrier created by the ordinance is perceived as being inconvenient and burdensome; it is therefore ignored by the Labor Board.

All City boards and commissions including the Labor – Management Relations Board, are required to file an annual report with the City Council. Any problems the board or commission experiences with its establishing ordinances are to be brought to the attention of the Council so they may be discussed and amended, altered, changed, scraped or replaced through further legislation.

Albuquerque Code of OrdinancesTo the best of my recollection the Labor Board has no history of complying with the reporting requirement. Very few boards and commissions make such reports. No reports are filed and the Mayor does not even request them. Reports would flow thorough the Mayor’s office and be directed to the Council as executive communications. The Council is also derelict in not requiring compliance with its ordinances.

Chapter 2: Government

Article 6: Public Boards, Commissions and Committees

(D) Report. At least once each year, every public board, commission or committee shall present a written report to the Mayor and Council of its activities for the past year and any recommendations as may be deemed appropriate.

Instead of addressing the recognized problems, the Labor Board refuses to seek guidance from the Council and muddles through, making rulings that are often contrary to the clear language of the ordinance.

At the Sept. 26, 2006, City Labor Board meeting, Assistant City Attorney Paula Forney-Thompson, center, between Office of Employee Relations Director Lawrence Torres, right, and his contracted assistant Paul Broome, left, complained to the Board saying that I could not photograph the meeting.

At the Sept. 26, 2006, City Labor Board meeting, Assistant City Attorney Paula Forney-Thompson, center, between Office of Employee Relations Director Lawrence Torres, right, and his contracted assistant Paul Broome, left, complained to the Board saying that I could not photograph the meeting. Before I could interject, three people all started to respond, all saying that the meeting was subject to the State’s Open Meetings Act and its provision to accommodate the press. Chairman Justin Pennington was the person whose voice prevailed and as Forney-Thompson muttered on, he gave me a big wink and a nod, indicating I would have nothing to say in the matter.

Before I could interject, three people all started to respond, all saying that the meeting was subject to the State’s Open Meetings Act and its provision to accommodate the press. Chairman Justin Pennington was the person whose voice prevailed and as Forney-Thompson muttered on, he gave me a big wink and a nod, indicating I would have nothing to say in the matter.

Later during the Sept. 2006 meeting, the Board’s Management representative Ruben Mirabal, left, Pennington and Union’s selection Debbi Lattimore, held a discussion where they complained about what they perceived as limitations placed on them by the ordinance, I rose to comment.

Later during the Sept. 2006 meeting, the Board’s Management representative Ruben Mirabal, left, Pennington and Union’s selection Debbi Lattimore, held a discussion where they complained about what they perceived as limitations placed on them by the ordinance, I rose to comment.I suggested that the Board was on the right track when they complained about the law and that they had the power to do something through the required reports to the mayor and council. I told them that they should pull the pin from the hand grenade and blow the ordinance up.

Forney-Thompson told the board’s clerk to hold a copy of the tape from the recording, because I had just threatened an act of terrorist violence against the Board. She was met with rolling eyes, shaking heads and snickers.

Forney-Thompson told the board’s clerk to hold a copy of the tape from the recording, because I had just threatened an act of terrorist violence against the Board. She was met with rolling eyes, shaking heads and snickers. Forney-Thompson and I have history. She represented the city when I sued over not being promoted to sergeant in 1988. She lied to the judge saying I had failed to exhaust my administrative remedies before going to court. The city had refused to respond to my appeal and, following the rules of the grievance procedure, I had continued up each step of the process after waiting the stated time limit for the administration to respond. I had played “the exhaustion of administrative remedies game” with the city before and in that case had written two letters for each step of the appeals process and I was covered. Forney-Thompson was correct that due process had not been followed and the city had not held a hearing; she had not indicated that the failure to do so lay solely upon the administration. However, the judge refused to listen, bought her lie and the case was dismissed. The city still refused to follow the due process hearing, ignoring my request for a grievance.

Forney-Thompson and I have history. She represented the city when I sued over not being promoted to sergeant in 1988. She lied to the judge saying I had failed to exhaust my administrative remedies before going to court. The city had refused to respond to my appeal and, following the rules of the grievance procedure, I had continued up each step of the process after waiting the stated time limit for the administration to respond. I had played “the exhaustion of administrative remedies game” with the city before and in that case had written two letters for each step of the appeals process and I was covered. Forney-Thompson was correct that due process had not been followed and the city had not held a hearing; she had not indicated that the failure to do so lay solely upon the administration. However, the judge refused to listen, bought her lie and the case was dismissed. The city still refused to follow the due process hearing, ignoring my request for a grievance. Forney-Thompson is married to Bruce Thompson who is also an attorney, currently serving in the City Council’s office. They are seen here together at a Council meeting as she speaks to him before leaving work late in the evening.

Forney-Thompson is married to Bruce Thompson who is also an attorney, currently serving in the City Council’s office. They are seen here together at a Council meeting as she speaks to him before leaving work late in the evening.They have been governmental lawyers for more than 20 years and have served in more jobs than I can keep up with. Between them they have served at the Albuquerque City Attorney’s office, the Attorney General’s office, State Risk Management, as Santa Fe City Attorney, and some places more than once.

Bruce Thompson, right, here with fellow Assistant City Attorney Charles Kolberg, represented the city before the Labor Board for several years; in the position his wife now holds.

Bruce Thompson, right, here with fellow Assistant City Attorney Charles Kolberg, represented the city before the Labor Board for several years; in the position his wife now holds. The City’s bus drivers union was in place when the City took over the privately owned and operated Albuquerque Bus Company in 1968. The Brotherhood of Local Engineers then represented the drivers. The city negotiated with the BLE, even though there was no ordinance in place. Federal law required the city to maintain the relationship with the union that was in place with the private company. The city is still trying to ignore the fact that federal law requires them to honor provisions of mandatory interest arbitration dispute resolution that came with the change 30 years ago.

The City’s bus drivers union was in place when the City took over the privately owned and operated Albuquerque Bus Company in 1968. The Brotherhood of Local Engineers then represented the drivers. The city negotiated with the BLE, even though there was no ordinance in place. Federal law required the city to maintain the relationship with the union that was in place with the private company. The city is still trying to ignore the fact that federal law requires them to honor provisions of mandatory interest arbitration dispute resolution that came with the change 30 years ago.Later, the BLE internally split their national union to more accurately reflect the workers they represented. The United Transportation Union was created to distinguish themselves from railroad engineers. Albuquerque bus drivers were then affiliated as Local 1745 of the national UTU.

In 1986, a bus driver, Robert Gutierrez, above right became Chairman of UTU, Local 1745. He would hold that elected position for 17 years. Gutierrez, right, prepares for an interview with then KOAT TV City Hall Reporter Karen McDaniels, left, in 1999. He was the longest serving head of a city union since adoption of the labor ordinance.

In 1986, a bus driver, Robert Gutierrez, above right became Chairman of UTU, Local 1745. He would hold that elected position for 17 years. Gutierrez, right, prepares for an interview with then KOAT TV City Hall Reporter Karen McDaniels, left, in 1999. He was the longest serving head of a city union since adoption of the labor ordinance.In 2003, the local drivers split from the parent organization, UTU, forming them self as the New Mexico Transportation Union.

Because there was no change in the leadership or make up of the local, and because UTU did not make a fight before the City’s L-MRB, there simply was a name change.

Over the years of Gutierrez’ leadership a minority faction of union members grew discontent with his representation.

A group of dissatisfied bus and van drivers aligned themselves with the national Teamsters union in 2006 and attempted to unseat NMTU as the exclusive bargaining agent. The Teamsters petitioned the City for an election and in spite of opposition from NMTU, the Labor Board ordered an election, not to decertify, but to change which organization would be the exclusive bargaining representative. As a result of the election, the drivers sided with the NMTU.

The City’s Transit Department’s Director Greg Payne, left, in 2006 promoted Gutierrez to serve in mid-management. Gutierrez, from his new position, was able to affect changes that, as union chairman, he had not previously been able to convince management to make.

The City’s Transit Department’s Director Greg Payne, left, in 2006 promoted Gutierrez to serve in mid-management. Gutierrez, from his new position, was able to affect changes that, as union chairman, he had not previously been able to convince management to make.Gutierrez still had a strong influence over the union, in part, because he was perceived as still being a driver who just happened to have changed jobs.

So, what’s wrong with this picture?

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Local 624, currently represents and is the exclusive bargaining unit for the City’s Blue Collar workers. AFSCME Local 624 challenged the NMTU to be the exclusive bargaining agent for bus and van drivers by filing with the Labor Board signatures to have an election to change the formally recognized union.

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Local 624, currently represents and is the exclusive bargaining unit for the City’s Blue Collar workers. AFSCME Local 624 challenged the NMTU to be the exclusive bargaining agent for bus and van drivers by filing with the Labor Board signatures to have an election to change the formally recognized union.The Labor Board had previously investigated and determined the appropriateness of the bus and van drivers in a particular bargaining unit and recognized NMTU as exclusive agent, just as they had established blue-collar workers and their exclusive representation to be AFSCME Local 624.

In response to AFSCME’s Petition, NMTU petitioned the labor board, demonstrating that the union represented 72 percent of the members of the bargaining unit by a showing of city payroll dues deduction.

NMTU is the exclusively certified union representing the group in negotiating contracts and in adjusting grievances, at least through the expiration of an existing contract with the city, which ends on June 30.

The Labor Board had to reject parts of the ordinance outright, specifically the existing majority status of NMTU, the fact that decertification is the means of removing a union as the exclusive bargaining agent.

Several legal issues about the propriety and nature of a vote were raised by NMTU before the Labor Board that were not fully addressed, including: the right of a legally recognized union to be protected from being taken over by another union that represents a completely different group of workers, under the city’s ordinance.

The Board ignored the meaning of the ordinance, did not hold a proper hearing and accepted the challenge of Local 624. The Board arranged for the League of Women Voters to conduct an election, which was held Friday April 25. The vote was 141-101 for AFSCME.

Assistant City Attorney Doris Duhigg, left, announced the League of Women Voters report.

Assistant City Attorney Doris Duhigg, left, announced the League of Women Voters report.Contrary to the belief of some union officials from both camps and the opinion of city labor officials, AFSCME may not immediately take over the union. The labor board accepted and ratified the April 25 election. The Labor Board sent its findings to the mayor for his signature. The Mayor signed, formally recognizing AFSCME as the bargaining unit on May 14.

However, the leadership of AFSCME and the city’s Office of Employee Relations Director Torres and Broome believe that the vote was the turning point. They were not dealing with the NMTU and may have started talking to ASFCME, prior to the Mayor’s signature as if they were the exclusive bargaining agent.

It won’t be quite that simple.

NMTU has signed a contract that is to take effect July 1. It includes an “assignability clause,” which locked down the contract by stating:

This agreement shall be binding upon the successors and assignees of the parties hereto, and no provisions, terms, or obligations herein contained shall be affected, modified, altered or changed in any respect whatsoever by any change of ownership or management by either party; or by any change, geographical or otherwise in the location or business of either party.It means that AFSCME and the City are bound to the new contract even though the union party’s name will not accurately reflect the new exclusive bargaining agent.

At the labor board meeting May 5, when NMTU attorney Paul Livingston read the “assignability clause,” he suggested that AFSCME might be bound to the ratified and signed three-year contract NMTU has with the city that goes into effect July 1. Broome and AFSCME’s attorney Shane Youtz, below right, made comments that it was not yet determined how the new union would proceed. Assistant City Attorney Paula Forney Thompson adamantly shook her head in agreement with Livingston’s sense of the meaning of the clause.

At the labor board meeting May 5, when NMTU attorney Paul Livingston read the “assignability clause,” he suggested that AFSCME might be bound to the ratified and signed three-year contract NMTU has with the city that goes into effect July 1. Broome and AFSCME’s attorney Shane Youtz, below right, made comments that it was not yet determined how the new union would proceed. Assistant City Attorney Paula Forney Thompson adamantly shook her head in agreement with Livingston’s sense of the meaning of the clause. AFSCME filed an ethics complaint against Mayor Martin Chávez and ABQ Ride Director Greg Payne charging that the city had given huge raises to fire, police the transportation unions and were only going to offer 2.6 percent raises to the AFSCME union locals. Insiders, well known to this blogger, who are in a position to know, but spoke on the condition that their identity not be revealed, say the claim is true. Further, should the new AFSCME representatives at the Transit Department succeed in reopening the contract that NMTU negotiated, ratified and the parties have signed, scheduled to go into effect July 1, the sources said that the offer would be 2.6 percent, in part because Payne “hates AFSCME.”

AFSCME filed an ethics complaint against Mayor Martin Chávez and ABQ Ride Director Greg Payne charging that the city had given huge raises to fire, police the transportation unions and were only going to offer 2.6 percent raises to the AFSCME union locals. Insiders, well known to this blogger, who are in a position to know, but spoke on the condition that their identity not be revealed, say the claim is true. Further, should the new AFSCME representatives at the Transit Department succeed in reopening the contract that NMTU negotiated, ratified and the parties have signed, scheduled to go into effect July 1, the sources said that the offer would be 2.6 percent, in part because Payne “hates AFSCME.”There seems to be agreement between AFSCME and the Office of Employee Relations that the NMTU ratified and signed contract is null and void.

“We are looking at taking legal action,” NMTU Chairman Fred Garcia said in an interview after the election. The union is pursuing several cases that have been pending before the labor board for as long as ten years. Garcia said that the new agreement had some of the newer drivers making more than a 25 percent increase over the life of the contract. But they voted for AFSCME Garcia said.

“We are looking at taking legal action,” NMTU Chairman Fred Garcia said in an interview after the election. The union is pursuing several cases that have been pending before the labor board for as long as ten years. Garcia said that the new agreement had some of the newer drivers making more than a 25 percent increase over the life of the contract. But they voted for AFSCME Garcia said.The 25 percent increase may only apply to newer drivers at the end of the contract and several other monetary items were surrendered away.

The failure of the Labor Board to schedule and hear prohibited practice cases may have contributed to a sense of discontent by the rank and file that led to the AFSCME effort to take over the bus drivers. NMTU attorney Paul Livingston said he was unsure how the outstanding cases that NMTU has pending before the board will be handled. However, at a Labor Board meeting on Monday, May 19, the Labor Board announced that because the Mayor had signed the letter certifying AFSCME, Local 624, as the choice of the Transit drivers’ bargaining unit, the NMTU had no “standing.” This precluded the scheduled hearing in a case that had been pending for more than two years.

In addition to the bus and van drivers, AFSCME also represents city workers in the Blue Collar, White Collar, Management, and Security Officers’ unions. The last three, the clerical, management, and officers unions have only minority membership. The city has an obligation to not recognize them for their failure to maintain a majority status. However, neither the Mayor, the Labor Relations Department, nor the Labor Board will take the required action to decertify the minority unions. Instead, they are engaging in illegal bargaining with unions that don’t represent a majority of their bargaining units.

My Take

My TakeLabor Relations Director Torres was an Open Space Ranger when the Airport Police and Park Rangers left AFSCME’s Albuquerque Officers Union, Local 1888, in about 1998 to join the Albuquerque Police Officers Association. AFSCME was a cooperative party in the separation believing that the airport and park law enforcers were better suited in the APOA, with other state-certified, gun-carrying, arrest-empowered cops.

Torres was the Open Space representative on the APOA’s contract negotiations team. He is seen here, right, listening to Mayor Jim Baca, left, with Chief Administrative Officer Lawrence Rael, second from the left, and the remaining members of the APOA’s negotiations team. Baca and Rael were trying to gain support for a quarter cent gross receipts transportation tax. The administration was fearful that the APOA might oppose the tax as they had opposed the quarter cent gross receipts “public safety” tax a couple of years earlier. What Baca and Rael failed to recall was the APOA had opposed the earlier tax because it was called a “public safety tax” and the union’s position was that public safety should not have a special tax, because they were “first, last and always” to be funded from the overall taxing formula.

Torres was the Open Space representative on the APOA’s contract negotiations team. He is seen here, right, listening to Mayor Jim Baca, left, with Chief Administrative Officer Lawrence Rael, second from the left, and the remaining members of the APOA’s negotiations team. Baca and Rael were trying to gain support for a quarter cent gross receipts transportation tax. The administration was fearful that the APOA might oppose the tax as they had opposed the quarter cent gross receipts “public safety” tax a couple of years earlier. What Baca and Rael failed to recall was the APOA had opposed the earlier tax because it was called a “public safety tax” and the union’s position was that public safety should not have a special tax, because they were “first, last and always” to be funded from the overall taxing formula. Torres has lately been claiming and telling people that I was his mentor and that everything he knows about labor management he learned from me. I have to defend myself as an instructor, what he says is partly true. Torres may have learned some things from me, especially negotiation tactics, but based on how he reads the labor ordinance and how he administers the city’s dealings with employee organizations, “Professor Bralley” has to fail student Torres for not learning the most important aspects of labor relations.

Torres has lately been claiming and telling people that I was his mentor and that everything he knows about labor management he learned from me. I have to defend myself as an instructor, what he says is partly true. Torres may have learned some things from me, especially negotiation tactics, but based on how he reads the labor ordinance and how he administers the city’s dealings with employee organizations, “Professor Bralley” has to fail student Torres for not learning the most important aspects of labor relations. Labor Board Chairman Justin Pennington, left, asked Torres what, if any, problems there were during the voting process at the AFSCME-NMTU April 25 election.

Labor Board Chairman Justin Pennington, left, asked Torres what, if any, problems there were during the voting process at the AFSCME-NMTU April 25 election.Torres did not answer directly or honestly, instead he stated. “We got through it.” He refused to change his answer when asked again and when he was asked a third time he only would say that they had experienced minor problems and issues that were not unexpected. Pennington gave up.

During the same April 30 Labor Board meeting, the Management Board member, Ruben Mirabal, left, moved acceptance of the New Mexico League of Women Voters election report. Groups composed like the labor board is, with a member selected by the unions, and one appointed by the mayor’s administration who jointly select a neutral chair, traditionally follow certain protocols. In this case, where the issue is one brought forward by an employee group, protocol dictates that the unions’ Board representative should make the motion, lest it appear that management has had some hand in the process. Apparently neither Mirabal, the city’s representative, nor Lattimore, right, the unions’ representative, knew about the protocol. Appearances are important, especially where there are accusations by the competing unions of collusion with the administration.

During the same April 30 Labor Board meeting, the Management Board member, Ruben Mirabal, left, moved acceptance of the New Mexico League of Women Voters election report. Groups composed like the labor board is, with a member selected by the unions, and one appointed by the mayor’s administration who jointly select a neutral chair, traditionally follow certain protocols. In this case, where the issue is one brought forward by an employee group, protocol dictates that the unions’ Board representative should make the motion, lest it appear that management has had some hand in the process. Apparently neither Mirabal, the city’s representative, nor Lattimore, right, the unions’ representative, knew about the protocol. Appearances are important, especially where there are accusations by the competing unions of collusion with the administration. Bus and drivers react to the Board's ruling, of accepting the election results and forwarding them to the Mayor for his action.

Bus and drivers react to the Board's ruling, of accepting the election results and forwarding them to the Mayor for his action.

As an outsider, it appeared to me, that NMTU had several problems:

With the removal of Gutierrez as chairman, the dynamism of the leadership was weakened and a less politically savvy group was left to face a growing hostile membership.

The minority of disgruntled bus drivers, instead of using its internal political power to successfully run their own slate of candidates in union elections, resorted to seeking out AFSCME, just as they had previously sought the Teamsters to represent them.

AFSCME, by its very nature is a predatory organization that is always willing to attack weakened groups of workers. AFSCME did not grow to have over 1.4 million members by being timid.

NMTU, when they broke from UTU also severed ties with the even larger group of unions, the AFL-CIO, which would have prohibited AFSCME from raiding a sister member union if the drivers were still associated with UTU.

There were several problems that the NMTU did not, and in some cases, could not address, which made them vulnerable, especially not being able to address prohibited practices.

The public fight over who should be the bargaining agent was a predictably nasty affair with charges and counter-charges.

President of AFSCME Council 18 Andrew Padilla, left, filed a private criminal complaint, according to Bernalillo County Metropolitan court online records, charging NMTU Chairman Garcia with two misdemeanors, assault and battery, for allegedly attacking him during a confrontation at the city’s Yale Blvd. bus facility. Garcia denied the charges in an interview for this posting. Court records show a jury trial is pending.

President of AFSCME Council 18 Andrew Padilla, left, filed a private criminal complaint, according to Bernalillo County Metropolitan court online records, charging NMTU Chairman Garcia with two misdemeanors, assault and battery, for allegedly attacking him during a confrontation at the city’s Yale Blvd. bus facility. Garcia denied the charges in an interview for this posting. Court records show a jury trial is pending.A former probationary employee claimed she was fired for trying to organize NMTU drivers into AFSCME. As a probationary employee, she was subject to termination without reason, though ABQ Ride officials, on and off the record indicated she was released for poor job performance. She was hired then by AFSCME to continue to organize.

There was a presentation by AFSCME operatives before the City Council where ministers from Albuquerque Interfaith Ministry spoke against NMTU claiming it was a city run union. They called the NMTU a “company” union.

Posters comparing NMTU with Osama Bin Laden and President George Bush as terrorists who got their positions by lying and cheating surfaced and made news when they were posted at bus yards. NMTU accused AFSCME operatives of the postings and AFSCME officials denied they were involved.

AFSCME filed a prohibited practice complaint with the Labor Board asserting that the city was illegally interfering by providing NMTU with assistance and support in denying AFSCME organizers access to Transit Department property.

The charge is very problematic. AFSCME admits that they were trying to get on city property to organize. The AFSCME officials are neither city employees nor bus drivers. Just because the NMTU officials are city employed bus drivers does not authorize them access or the right to engage in activity to counter the AFSCME effort.

According to the complaint, City Security guards were present and did not act immediately. They might have prohibited the physical confrontation from occurring.

In the spirit of the First Amendment, such confrontations are bound to happen and I have no direct knowledge of whether the stand off was on city property or on a public sidewalk. The crack in the concrete would make a difference.

NMTU held union activities on city property, specifically a cook out. AFSCME also secured permission to have its own “barbeques” and held at least two such events. Permitting such events on the job site should not be allowed by the city administration.

In an interview Labor Board Member Debbi Lattimore, left, the labor-selected Board member, after the acceptance of the vote, acknowledged that the vote should have been one for decertification. However, she said, because she had voted in the earlier case involving the Teamsters’ attempt to take over the NMTU to allow the question to be about who should be the representative, she felt bound by her earlier position.

In an interview Labor Board Member Debbi Lattimore, left, the labor-selected Board member, after the acceptance of the vote, acknowledged that the vote should have been one for decertification. However, she said, because she had voted in the earlier case involving the Teamsters’ attempt to take over the NMTU to allow the question to be about who should be the representative, she felt bound by her earlier position.This year’s round of negotiations are not negotiations at all. They are fraught with serious misconduct by the management players. The City has not followed the Labor ordinance in many respects. They have not entered into “good faith bargaining” where the union makes proposals with the city countering and the parties sitting down to work out an agreement.

Instead, this year the negotiations were conducted by the city bringing large amounts of money, announcing the huge sums in what appears to be a successful public relations campaign to get rank and file to ignore the critical language in favor of the money.

Albuquerque Code of OrdinancesThis is not what happened.

Chapter 3: City Employees

Article 2: Labor – Management Relations

§ 3-2-13 Negotiating Procedures

(C) Procedure for Negotiations.

- Negotiations will be conducted as provided below and will take place at the facilities and at a time mutually agreed to by the negotiating teams.

- All negotiations will be held in closed sessions.

- Negotiations will start with the negotiating team of the party requesting negotiations delivering their proposed changes, one section or subsection at a time. Each section will be read out loud with the changes and the reasons therefore indicated in some detail. This procedure will lessen the chances of misunderstandings and increase the chances for acceptance. This procedure will continue to be followed until the entire employee organization proposal has been presented.

- Upon complete presentation of the proposal, the other negotiating team will present their counter proposal in the same manner.

- Thereafter, each side will take turns presenting counter proposals with supporting data until agreement is reached a section at a time. It may be necessary to leave one section and go on to another in order to get a new look at the one passed up.

- Negotiating sessions will proceed with deliberate speed, but recesses and study sessions may be called for by either side. Prior to recess, the reconvening time will be agreed upon.

NMTU requested an opening of negotiations, but nothing happened for several weeks.

AFSCME petitioned the Labor Board instead of addressing it to the mayor for an election to be the exclusive representative of the transportation workers. Broome claimed to be acting for the mayor in accepting the petition.

Forney-Thompson argued to the Labor Board that because there was a challenge to NMTU that the City would not enter into negotiations until an election was resolved. There are several problems with Forney-Thompson’s contentions: NMTU was the exclusive bargaining agent at that time and until the election process and the mayor's officially recognizing a different representative; not dealing with NMTU was illegal.

NMTU filed a petition with the Labor Board contesting AFSCME’s 35 percent interest cards by providing a showing of 73 percent membership through city payroll due deductions.

Within two hours of the filing of the petition, on a Friday, Employee Relations Director Torres called NMTU Chairman Garcia and wanted to meet on the following Monday at 10:00 am to negotiate. Torres said they could wrap up the negotiations on that Monday.

The City opened with NMTU by demanding that all unresolved prohibited practice complaints be abandoned as a pre-condition of negotiations.

Broome insisted that all non-economic issues be settled before there was any disclosure of how much money the city was offering. The city had offered nothing in writing, so the parties broke so the city could formalize their offer.

On Wednesday the parties met and Broome made a take it or leave it offer. The City negotiators gave an ultimatum; agree to the contract immediately or face the possibility that ASFCME would win the election.

The ordinance is specific. It is illegal for an elected or appointed official, including the Mayor, to attempt to influence negotiations.

§ 3-2-9 Prohibited Practices

(C) It shall be a prohibited practice for any elected or appointed official of the city government or for any employee organization, group of city employees or individual city employee to attempt to influence negotiations or to interfere with the normal progress of negotiations between the duly authorized negotiating teams of the city government and of the employee organization.

Paul Broome, above, contends before the Labor Board that there was “good faith bargaining” by pointing to the boilerplate language that states:

Paul Broome, above, contends before the Labor Board that there was “good faith bargaining” by pointing to the boilerplate language that states:The parties have negotiated in good faith and have reached a full agreement on all issues.

It has always been my belief that the City’s Labor-Management Relations Ordinance was retaliatory and preemptive for the 1970 wildcat strike and the physical injury to Deputy Chief of Police Albert Swallows. The city hired an outside industrial relations firm to train supervisors on how to deal with unions.

It has always been my belief that the City’s Labor-Management Relations Ordinance was retaliatory and preemptive for the 1970 wildcat strike and the physical injury to Deputy Chief of Police Albert Swallows. The city hired an outside industrial relations firm to train supervisors on how to deal with unions.The ordinance is one-sided, leaning towards management.

The language could be clearer, but seems to be intentionally convoluted and confusing so it may be subject to various interpretations.

Though the ordinance has strict time limits, when it comes to following them cases rarely get scheduled in a timely manner and even more rarely get heard. Even when cases are heard, and still more rarely, when they are decided, the Labor Board hardly ever issues a written decision. The ordinance, however, requires hearings to be held “as soon as possible” and strictly requires a written decision with findings of fact and conclusions of law.

The Labor Board frequently delays hearings, hoping either to have the city and unions work out a solution on their own, discourage the union from proceeding, or simply ignore issues forever.

Yet, if an allegation of a strike is made against a union, or if strike-like activity or an employee work-action occurs, watch how fast the City administration will bring the Labor Board into session. Of course, the city administers the Labor Board, so the Board almost always does what the city administration asks. In the case of the AFSCME-NMTU election, for example, it was a city “motion” that asked the Labor Board to schedule the election, without ever giving the NMTU a chance to show that the only election that was allowed by the Ordinance was a “decertification” election, not the representation election the city requested in its motion.

A prohibited practice complaint brought by a union is the reverse equivalent of a workers strike; it alleges the failure of the city’s administration to uphold their end of the working contract.

Since Mayor Chávez has formally recognized AFSCME as the exclusive bargaining agent other questions arise:

What happens to the existing contract that the City has with NMTU and is scheduled to expire June 30?

NMTU has already timely negotiated a contract by ordinance that begins July 1. What affect does the AFSCME take over have on that document?

At a May 19 Labor Board meeting Broome characterized the April 25 election, as a decertification election. If, in fact it was a decertification election, then the ordinance requires a one-year moratorium in the collective bargaining process and there would be no contract in existence.

I don’t often agree with Broome, but on this point, I do. The ordinance allows only for a decertification election.

After one year, AFSCME, NMTU, or any other employee group may petition the mayor for recognition to be the collective bargaining agent.

Broome has been overruled; AFSCME is the new collective bargaining agent for transit drivers.

Employee relations, negotiations and even deciding the proper workers’ representatives are rough and tumble activities, not for the faint of heart.

Employee relations, negotiations and even deciding the proper workers’ representatives are rough and tumble activities, not for the faint of heart.However, where an ordinance exists, even when it is as messed up as it is here, strict compliance must still be applied.

It seems that instead of fixing the ordinance, through the legislative process, the city and some unions, especially AFSCME, which has a long history with the city of making up new rules when the ordinance is an impediment, rather not do things legally.

4 comments:

ATTENTION: UTU AND NMTU... The fiduciary duty is a legal relationship of confidence or trust between two or more parties, most commonly a fiduciary or trustee and a principal or beneficiary. One party, for example a corporate trust company or the trust department of a bank, holds a fiduciary relation or acts in a fiduciary capacity to another, such as one whose funds are entrusted to it for investment. In a fiduciary relation one person justifiably reposes confidence, good faith, reliance and trust in another whose aid, advice or protection is sought in some matter. In such a relation good conscience requires one to act at all times for the sole benefit and interests of another, with loyalty to those interests.

“ A fiduciary is someone who has undertaken to act for and on behalf of another in a particular matter in circumstances which give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence.[1] ”

A fiduciary duty [1] is the highest standard of care at either equity or law. A fiduciary (abbreviation fid) is expected to be extremely loyal to the person to whom he owes the duty (the "principal"): he must not put his personal interests before the duty, and must not profit from his position as a fiduciary, unless the principal consents. The word itself comes originally from the Latin fides, meaning faith, and fiducia, trust.

In English common law the fiduciary relation is arguably the most important concept within the portion of the legal system known as equity. In the United Kingdom, the Judicature Acts merged the courts of Equity (historically based in England's Court of Chancery) with the courts of common law, and as a result the concept of fiduciary duty also became usable in common law courts.

When a fiduciary duty is imposed, equity requires a stricter standard of behavior than the comparable tortious duty of care at common law. It is said the fiduciary has a duty not to be in a situation where personal interests and fiduciary duty conflict, a duty not to be in a situation where his fiduciary duty conflicts with another fiduciary duty, and a duty not to profit from his fiduciary position without express knowledge and consent. A fiduciary cannot have a conflict of interest. It has been said that fiduciaries must conduct themselves "at a level higher than that trodden by the crowd"[2] and that "[t]he distinguishing or overriding duty of a fiduciary is the obligation of undivided loyalty."[3]

there is absolutely nothing wrong with this picture. If you notice the banner on top of the buses one says "66" the other "Blueline". The blueline is changing lanes because it has to. the blueline runs through Lomas Blvd which is to the left. While the 66remains in its lane

There is absolutely nothing wrong with this picture. If you notice the banners on top of the buses one says "66" the "Blueline", the buses are both eastbound. The blueline must get onto the other lane to proceed with its route which is Lomas Blvd, on the left. Whilw the 66 continues east bound in its own lane. Thank You!!!!!!!

The blueline must change lanes in order to continue its route, through Lomas Blvd

Post a Comment