What’s Wrong With This Picture?

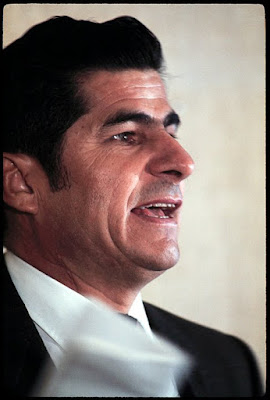

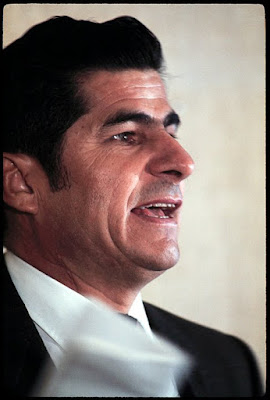

Reies López Tijerina: 47 Years

Tijerina, who lead the Hispanic Land-Grant movement, of the mid to late 1960s, passed away today from natural causes in an El Paso Hospital according to Russell Contreras, who covers the Southwest for Associated Press as a reporter/photographer.

He was 88.

Tijernia was born in a field where his mother was a migrant picker in Falls City, Texas.

This post starts at the end:

Tijerina spent most of his last few years in Mexico and El Paso, Texas.

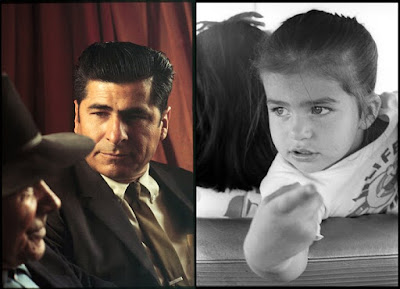

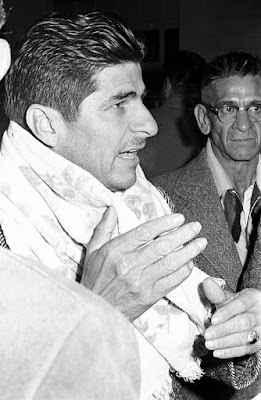

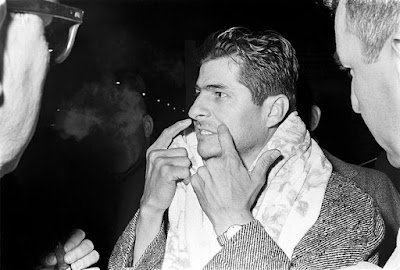

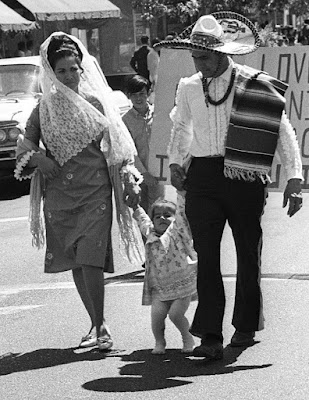

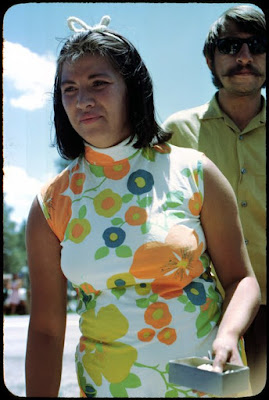

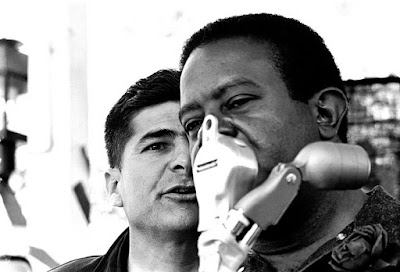

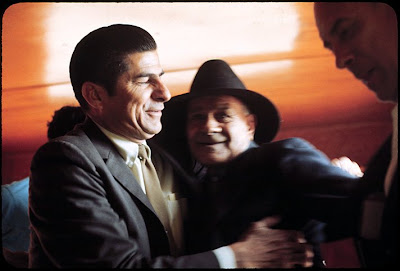

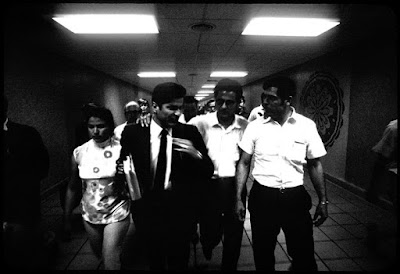

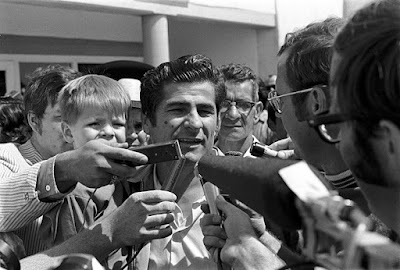

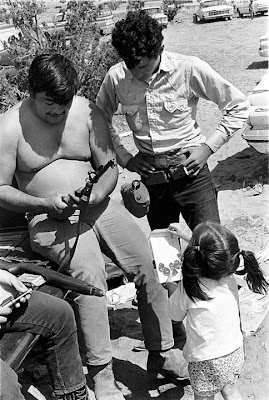

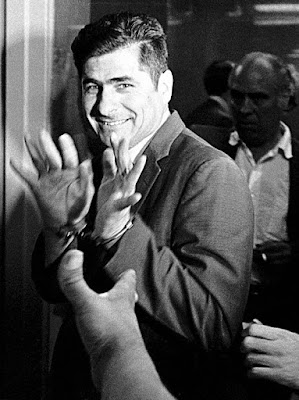

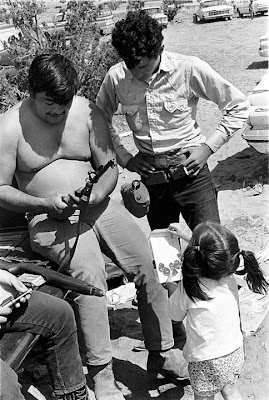

This is Reies López Tijerina and his 30-month old daughter Isabel. Isabel would play a crucial role in the following story.

This is Reies López Tijerina and his 30-month old daughter Isabel. Isabel would play a crucial role in the following story.

You may click on any picture and see it enlarged.

Forty years ago, I was in Federal District Court in Albuquerque testifying for both the prosecution and defense, about events that unfolded and became the end of Tijerina's public "militant" career. He was a charismatic leader of a movement in the states that were formed from the land that was once Mexico and captured during the Mexican-American war of 1846-48.

I spent eight days with Tijerina in New Mexico and Washington, D.C., in early June 1969 culminating when he and his wife Patsy were arrested for burning federal property and his resisting arrest by assaulting a federal law enforcement officer.

The underlying issues leading up to these events are complex and convoluted. I by no means attempt to chronicle the history of this man, the land grant movement, or the broader issues of the ethnic politics or culture of our region. Those issues are well documented in books about Tijerina, including:

Michael Jenkinson's 1968, "Tijerina land grant conflict in New Mexico",

Peter Nabokov's 1969, "Tijerina and the Courthouse Raid",

Richard Gardner's 1970, "Grito! Reies Tijerina and the New Mexico land grant war of 1967",

Patricia Bell Blawis', 1971, "Tijerina and the land grants; Mexican Americans in struggle for their heritage,"

Richard Griswold del Castilo‘s 1992, “The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict“,

Francisco Arturo Rosales' 1995, "Chicano!: the history of the Mexican American civil rights

movement",

Rudy V. Busto's 2005, "King Tiger: The Religious Vision of Reies Lopez Tijerina",

George Mariscal's 2005, "Brown-eyed children of the sun: lessons from the Chicano movement, 1965-1975",

Francisco Arturo Rosales' 2007, "Dictionary of Latino civil rights history", and

Tijerina's autobiography, "They Called Me "King Tiger": My Struggle for the Land and Our Rights," the 2000 English translated version of his earlier Spanish edition.

Tijerina donated his papers to the University of New Mexico's University Libraries, Center for Southwest Research in 2005 and may be viewed at the Anderson Reading room.

If one makes an Internet search the events of 1969 are non-existent or shallow, incomplete and misdirected. Some sources explain that Tijerina went to federal prison, but ignore telling which crimes he was convicted or correctly identifying the terms of the sentence.

This post deals with photographs I made of Tijerina's activities from 1968 to 1972. The color photographs have never before been published or displayed.

United Press International, the Associated Press, The Albuquerque News, and Newsweek previously published some of this work. Please look at the link because I try not to repeat those pictures here. You will have to scroll down a ways to get to the story.

So what’s wrong with this picture?

Originally known as the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, the Alianza Federal de los Pueblos Libres, as translated by its founder Reies López Tijerina to mean, the Alliance of free City-States.

Originally known as the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, the Alianza Federal de los Pueblos Libres, as translated by its founder Reies López Tijerina to mean, the Alliance of free City-States.

Reies López Tijerina: 47 Years

Tijerina, who lead the Hispanic Land-Grant movement, of the mid to late 1960s, passed away today from natural causes in an El Paso Hospital according to Russell Contreras, who covers the Southwest for Associated Press as a reporter/photographer.

He was 88.

Tijernia was born in a field where his mother was a migrant picker in Falls City, Texas.

This post starts at the end:

Tijerina spent most of his last few years in Mexico and El Paso, Texas.

This is Reies López Tijerina and his 30-month old daughter Isabel. Isabel would play a crucial role in the following story.

This is Reies López Tijerina and his 30-month old daughter Isabel. Isabel would play a crucial role in the following story.You may click on any picture and see it enlarged.

Forty years ago, I was in Federal District Court in Albuquerque testifying for both the prosecution and defense, about events that unfolded and became the end of Tijerina's public "militant" career. He was a charismatic leader of a movement in the states that were formed from the land that was once Mexico and captured during the Mexican-American war of 1846-48.

I spent eight days with Tijerina in New Mexico and Washington, D.C., in early June 1969 culminating when he and his wife Patsy were arrested for burning federal property and his resisting arrest by assaulting a federal law enforcement officer.

The underlying issues leading up to these events are complex and convoluted. I by no means attempt to chronicle the history of this man, the land grant movement, or the broader issues of the ethnic politics or culture of our region. Those issues are well documented in books about Tijerina, including:

Michael Jenkinson's 1968, "Tijerina land grant conflict in New Mexico",

Peter Nabokov's 1969, "Tijerina and the Courthouse Raid",

Richard Gardner's 1970, "Grito! Reies Tijerina and the New Mexico land grant war of 1967",

Patricia Bell Blawis', 1971, "Tijerina and the land grants; Mexican Americans in struggle for their heritage,"

Richard Griswold del Castilo‘s 1992, “The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict“,

Francisco Arturo Rosales' 1995, "Chicano!: the history of the Mexican American civil rights

movement",

Rudy V. Busto's 2005, "King Tiger: The Religious Vision of Reies Lopez Tijerina",

George Mariscal's 2005, "Brown-eyed children of the sun: lessons from the Chicano movement, 1965-1975",

Francisco Arturo Rosales' 2007, "Dictionary of Latino civil rights history", and

Tijerina's autobiography, "They Called Me "King Tiger": My Struggle for the Land and Our Rights," the 2000 English translated version of his earlier Spanish edition.

Tijerina donated his papers to the University of New Mexico's University Libraries, Center for Southwest Research in 2005 and may be viewed at the Anderson Reading room.

If one makes an Internet search the events of 1969 are non-existent or shallow, incomplete and misdirected. Some sources explain that Tijerina went to federal prison, but ignore telling which crimes he was convicted or correctly identifying the terms of the sentence.

This post deals with photographs I made of Tijerina's activities from 1968 to 1972. The color photographs have never before been published or displayed.

United Press International, the Associated Press, The Albuquerque News, and Newsweek previously published some of this work. Please look at the link because I try not to repeat those pictures here. You will have to scroll down a ways to get to the story.

So what’s wrong with this picture?

Originally known as the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, the Alianza Federal de los Pueblos Libres, as translated by its founder Reies López Tijerina to mean, the Alliance of free City-States.

Originally known as the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, the Alianza Federal de los Pueblos Libres, as translated by its founder Reies López Tijerina to mean, the Alliance of free City-States.

Founded in 1962 the Alliance was characterized by the establishment press as a militant Spanish American group.

Tijerina and the Alianza made claims to land grants based on provisions of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hildalgo ending the Mexican-American War. The U.S. Senate struck provisions for land grants from the treaty, however the New Mexico State Constitution addresses treaty provisions for land grants to remain intact as issued by the Spanish crown:

Despite efforts to resolve land grant claims that, included a series of Federal Court cases heard in 1891, and eventually appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which said the matter, because it was a treaty, a Congressional issue; Congress has never addressed or tried to clarify the issue.

The issue has been kept alive and is repeatedly submitted to Congress, but the bill never makes it through a committee hearing. In the practical sense it is an issue unlikely to be resolved.

In the summer of 1966, Tijerina led a group of followers on a three-day march from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to present Alianza land grant demands to New Mexico Governor Jack Campbell.

In the summer of 1966, Tijerina led a group of followers on a three-day march from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to present Alianza land grant demands to New Mexico Governor Jack Campbell.

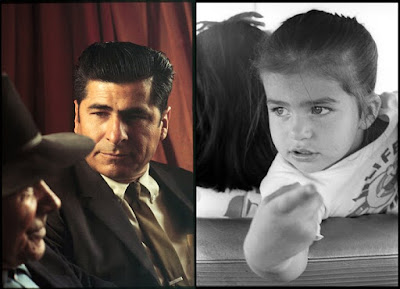

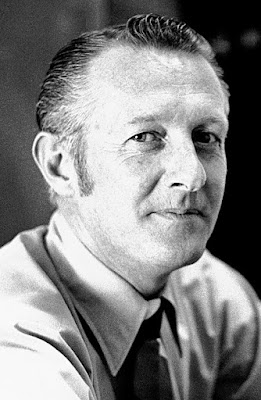

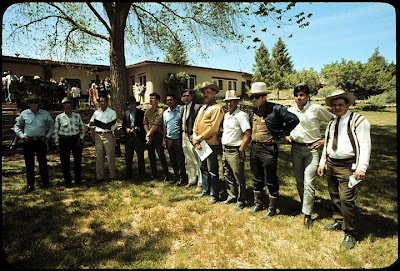

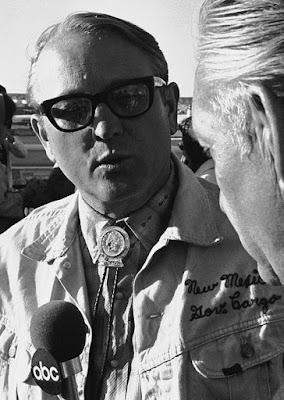

The Alianza also met with newly elected New Mexico Governor David F. Cargo, seen here during the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970.

The Alianza also met with newly elected New Mexico Governor David F. Cargo, seen here during the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970.

On October 22, 1966, the Alianza Federal de Mercedes held a convention at the Echo Amphitheater campground in the Carson National Forest, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. The Alianza claimed the property to be the Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant taken from the people and illegally under the control of the United States.

On October 22, 1966, the Alianza Federal de Mercedes held a convention at the Echo Amphitheater campground in the Carson National Forest, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. The Alianza claimed the property to be the Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant taken from the people and illegally under the control of the United States.

Two U.S. Forest workers tried to collect campground user fees from the group. The land grant’s marshals seized rangers Walter Taylor and Phil Smith and their vehicles.

A "mock" trial was commenced and rangers were convicted of trespass and being a nuisance. They were given suspended sentences and were released. Their trucks were "impounded."

On June 5, 1967, Tijerina led the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid." The purpose was to free some Alianza members from jail who had been arrested at an earlier event. Ironically, the men were freed and had left the courthouse shortly before the jailbreak occurred.

On June 5, 1967, Tijerina led the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid." The purpose was to free some Alianza members from jail who had been arrested at an earlier event. Ironically, the men were freed and had left the courthouse shortly before the jailbreak occurred.

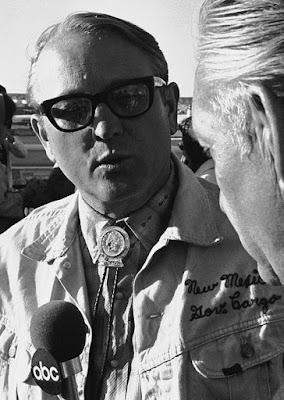

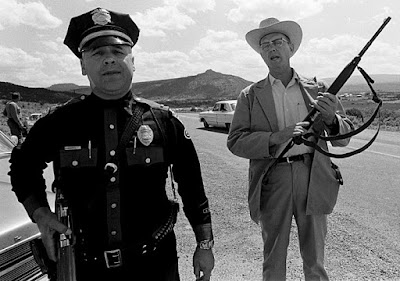

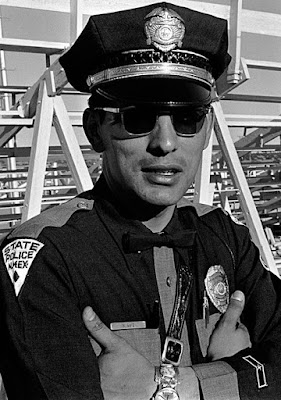

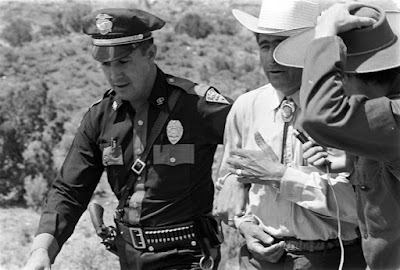

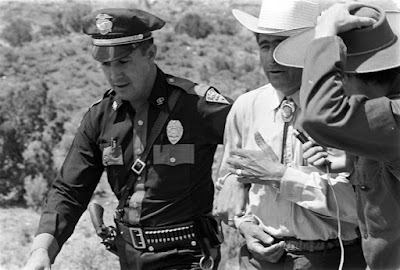

During the "raid" two law enforcement officers were shot: New Mexico State Police Officer Nick Saiz, seen here at the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970, and Rio Arriba County Jailer Eulogio Salazar. Tijerina was charged with shooting Salazar twice, once in the jaw.

During the "raid" two law enforcement officers were shot: New Mexico State Police Officer Nick Saiz, seen here at the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970, and Rio Arriba County Jailer Eulogio Salazar. Tijerina was charged with shooting Salazar twice, once in the jaw.

Associated Press Writer Larry Calloway was in the courthouse in a phone booth filing his story to the AP office in Albuquerque when gunfire erupted. Calloway has written at length about his experience; he was kidnapped and held by a couple of the raiders.

Salazar was abducted from in front of his home while opening his gate and was later found murdered in his car. Suspicion immediately turned to Tijerina and the Alianza. The investigation was short lived. Several members of the Alianza were arrested, but all could account for their whereabouts at the time of the murder and no one was charged. A law enforcement official close to the investigation at the time told me some undisclosed Constitutional issue made the case impossible to pursue, though police believe they knew what happened. New Mexico District Judge Joe Angle slapped a gag order on government officials, from the governor on down through law enforcement, to not comment about the case or investigation. Neither Tijerina nor the Alianza were involved.

Salazar was abducted from in front of his home while opening his gate and was later found murdered in his car. Suspicion immediately turned to Tijerina and the Alianza. The investigation was short lived. Several members of the Alianza were arrested, but all could account for their whereabouts at the time of the murder and no one was charged. A law enforcement official close to the investigation at the time told me some undisclosed Constitutional issue made the case impossible to pursue, though police believe they knew what happened. New Mexico District Judge Joe Angle slapped a gag order on government officials, from the governor on down through law enforcement, to not comment about the case or investigation. Neither Tijerina nor the Alianza were involved.

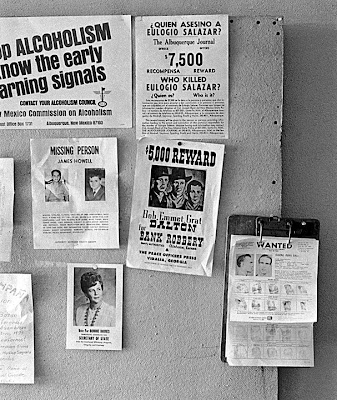

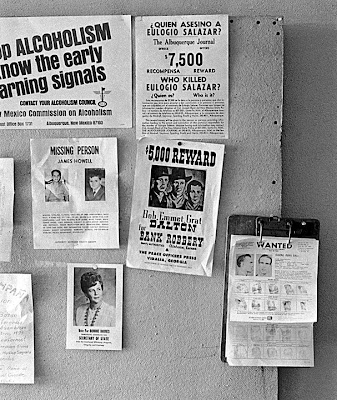

The Albuquerque Journal posted a $7,500 reward. Years later the reward poster still adorned law enforcement office walls.

The Albuquerque Journal posted a $7,500 reward. Years later the reward poster still adorned law enforcement office walls.

Tijerina and others were tried in Federal court. The trial venue was changed to Las Cruces in Doña Ana County at the Federal Courthouse before Judge Howard Bratton.

Reies López Tijerina, Cristobal López Tijerina, Jerry Noll, Ezekial Dominguez and Alfonso Chavez were convicted to varying degrees of assault of the two rangers and conversion (stealing) of two forest service trucks. The jury was deadlocked on the conspiracy count on all defendants and the judge ordered a mistrial.

Tijerina was convicted of assaulting the two rangers and acquitted of stealing the forest service trucks. He was sentenced to two years in prison and five years of probation.

Tijerina and Noll were also found to be in contempt of court for having violated a gag order by talking about the case before the trial at an Alianza convention.

Tijerina and Noll were sentenced to 30-days for the contempt.

Tijerina posted a $10,000 bond and was released pending the out come of an appeal.

Tijerina and his fellow defendants appealed the conviction and contempt to United States 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, Colorado, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied Writs of Certiorari rejecting hearing the issues.

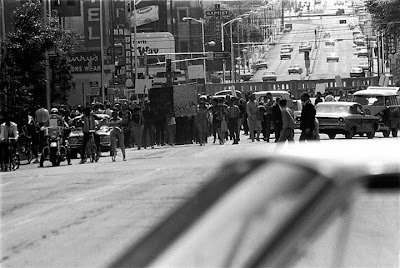

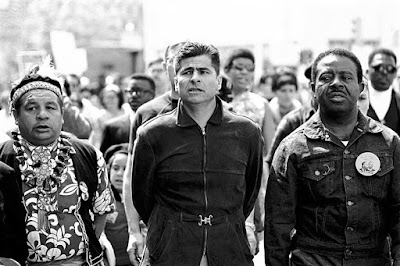

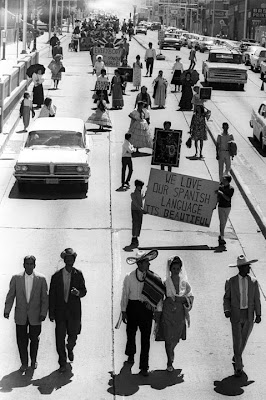

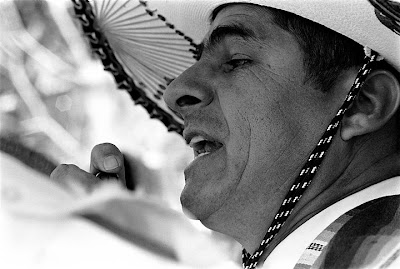

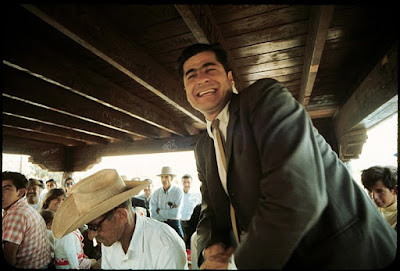

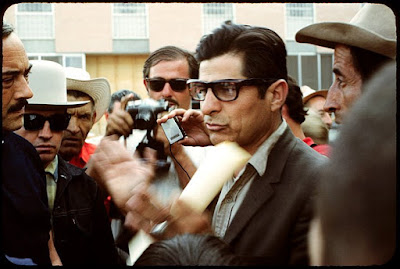

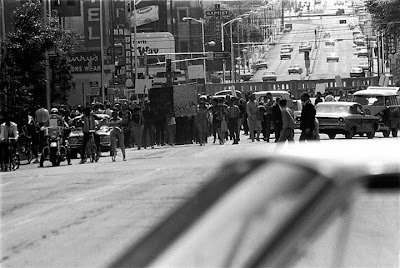

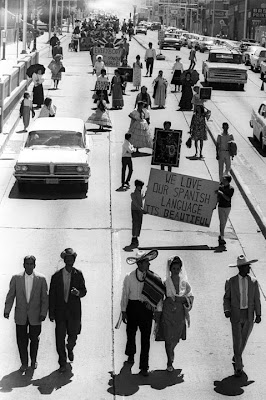

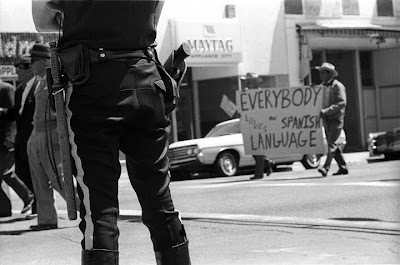

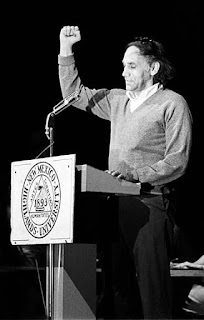

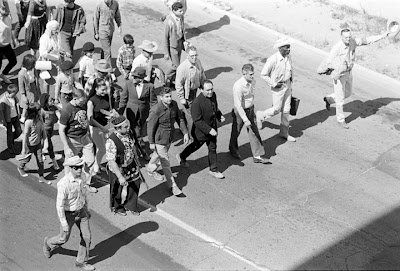

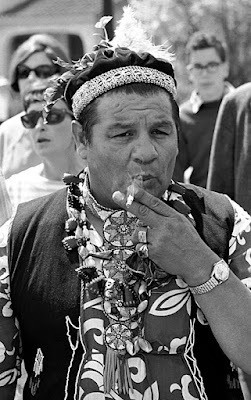

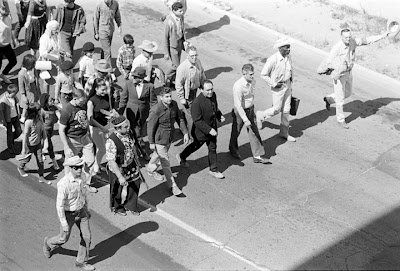

Saturday May 17, 1968, the Poor People's March, Albuquerque, N.M.

Saturday May 17, 1968, the Poor People's March, Albuquerque, N.M.

The Poor People's March, started as an idea of the late Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Tijerina was chosen by King to be a representative of the Hispanic delegation. His selection was controversial, with some claiming that the Alianza represented land retention and not poor people as typified by southern blacks. However King's vision for the march was not limited to blacks, but was to include all "poor people." He also included, Native Americans, residents of Appalachia, and any other groups deemed poor.

The Poor People's March, started as an idea of the late Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Tijerina was chosen by King to be a representative of the Hispanic delegation. His selection was controversial, with some claiming that the Alianza represented land retention and not poor people as typified by southern blacks. However King's vision for the march was not limited to blacks, but was to include all "poor people." He also included, Native Americans, residents of Appalachia, and any other groups deemed poor.

This was the western contingent that started in Los Angeles and worked its way to Washington, D.C.

Marchers passed through Albuquerque, from Dennis Chavez Park to the Old Town Plaza.

Marchers passed through Albuquerque, from Dennis Chavez Park to the Old Town Plaza.

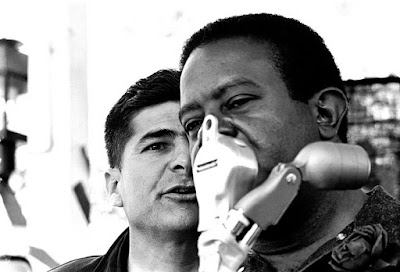

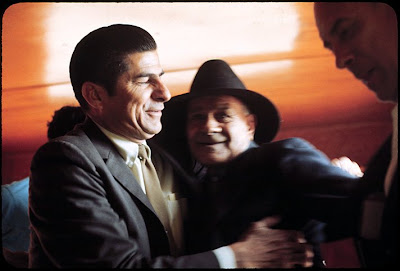

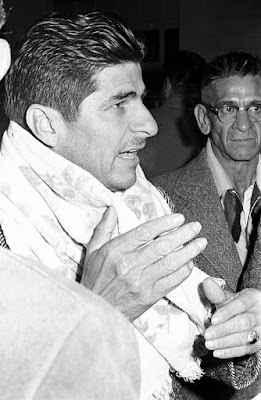

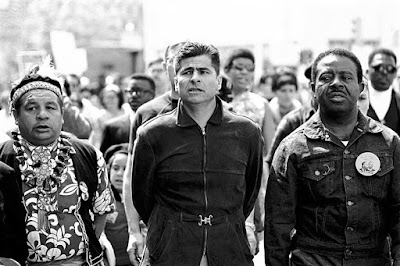

Tijerina offers the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference water from a canteen while marching through downtown.

Tijerina offers the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference water from a canteen while marching through downtown.

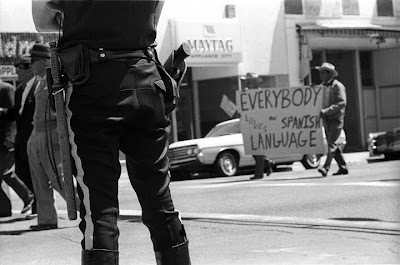

Police provided an escort common to such parades and maintained surveillance in the wake of King's April 4, 1968, assassination.

Police provided an escort common to such parades and maintained surveillance in the wake of King's April 4, 1968, assassination.

At Old Town, Tijerina whispers in Abernathy's ear during his speech.

At Old Town, Tijerina whispers in Abernathy's ear during his speech.

The Poor People's March ended in Washington, D.C. on the South Mall where the marchers took up residence in a complex of tents and temporary shelters that was called, "Resurrection City." The protesters spent about six weeks on the mall from mid May until late June when federal workers razed the "City."

Tijerina would lead a group of "Resurrection City" residents on a "raid" on the United States Supreme Court building on May 29.

In 1968 the Alianza created a political arm, the People’s Constitutional Party. Running for governor, Tijerina led a slate of candidates for state offices.

The State Supreme Court ruled that Tijerina could not remain on the ballot because of his federal felony conviction.

In the State trial for the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid" case charges against Tijerina were severed from the nine other defendants.

The charges of shooting Rio Arriba County Jailer Eulogio Salazar were initially dropped due to his death.

Tijerina fired his court appointed attorney and Second Judicial District Judge Paul Larrazolo granted his motion to represent himself. He represented himself on the three remaining charges: kidnapping, false imprisonment and assault on a jail.

First Judicial District Attorney Alfonso Sanchez prosecuted the case. Sanchez had been one of the targets of the raid.

The trial lasted a month and on December 13, the jury acquitted him.

Sanchez lost reelection as District Attorney in the November election and left office the last day of 1968.

Albuquerque police and fire departments were dispatched to an explosion.

Albuquerque police and fire departments were dispatched to an explosion.

The vehicle belonging to Alianza Vice President Santiago Anaya, below right, was destroyed by a bomb in a parking lot next to the Alianza headquarters at 1010 3rd St. N.W. Albuquerque, N.M.

The vehicle belonging to Alianza Vice President Santiago Anaya, below right, was destroyed by a bomb in a parking lot next to the Alianza headquarters at 1010 3rd St. N.W. Albuquerque, N.M.

Scattered wreckage was found several blocks away.

Scattered wreckage was found several blocks away.

A military ordnance disposal unit checked other vehicles for additional bombs.

A military ordnance disposal unit checked other vehicles for additional bombs.

The bombing was only one of a series of blasts against: the Alianza headquarters, members’ vehicles, and homes.

Albuquerque Police Department Detective Pat Gerber investigated this bombing. No arrest was made.

Albuquerque Police Department Detective Pat Gerber investigated this bombing. No arrest was made.

The string of bombings was chronicled by Peter Montagu in the Sept. 1969 The New Mexico Review's and reprinted in a Special Issue of El Grito Del Norte.

The NBC (National Broadcasting Company) television network's newsmagazine "First Tuesday" had a segment reported by host Sander Vanocur entitled, "The Most Hated Man in New Mexico" about Reies López Tijerina.

In the program Tijerina spoke of plans to hold an Alianza convention celebrating the second anniversary of the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid." Tijerina said that during the celebration, participants were going to confront the federal government, specifically, the Forest Service by possibly driving sheep and cattle onto National Forest land in symbolic protest of lost ancestral lands.

On May 12, 1969, I approached Tijerina with a proposal to do a photo story on his activities during the early part of June. He said no.

On May 12, 1969, I approached Tijerina with a proposal to do a photo story on his activities during the early part of June. He said no.

I followed him into his office and saw the photo, above, I had taken from him with Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference and Chief Beeman Logan, left, a leader of the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians from New York State at the May 17, 1968, Poor People's March. I pointed out the photo as being one I had taken. He questioned whether I shot the picture. I took the picture off the wall and showed him the back of the print had my rubberstamped name on it. He stated that it was his favorite photograph of himself and agreed to let me travel with him.

I followed him into his office and saw the photo, above, I had taken from him with Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference and Chief Beeman Logan, left, a leader of the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians from New York State at the May 17, 1968, Poor People's March. I pointed out the photo as being one I had taken. He questioned whether I shot the picture. I took the picture off the wall and showed him the back of the print had my rubberstamped name on it. He stated that it was his favorite photograph of himself and agreed to let me travel with him.

He told me he wanted a copy of all the photographs I took. I told him that that did not sound reasonable because my style was to shoot a lot of film then to select the best shot from the many to print. We agreed that I would give him a choice and make him 150 prints for his personal non-publication use.

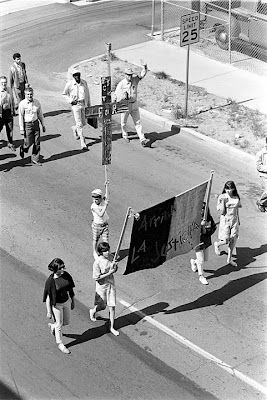

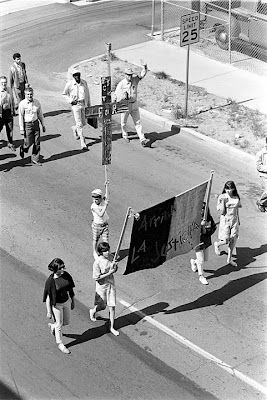

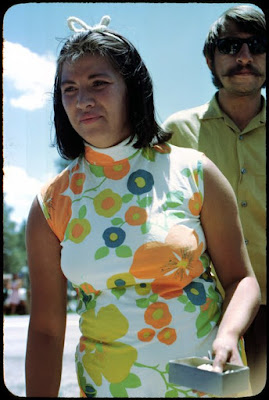

The Alianza sponsored a Spanish Language Parade from the University of New Mexico to the Old Town Plaza in Albuquerque.

The Alianza sponsored a Spanish Language Parade from the University of New Mexico to the Old Town Plaza in Albuquerque.

The parade celebrated the 429th anniversary of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's 1540 expedition into what is now New Mexico.

The parade celebrated the 429th anniversary of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's 1540 expedition into what is now New Mexico.

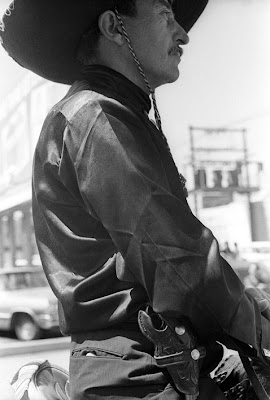

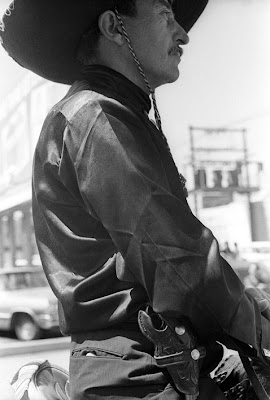

Jose "Duke" Aragon openly wore a .22 caliber pistol on his hip during the parade. The pistol would be seen later when it was fired at the Forest Service sign burning incident near Gallina.

Jose "Duke" Aragon openly wore a .22 caliber pistol on his hip during the parade. The pistol would be seen later when it was fired at the Forest Service sign burning incident near Gallina.

A flier about the event announced that Aragon's art work would be featured.

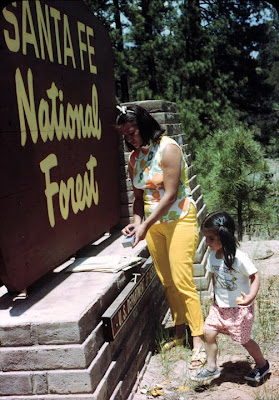

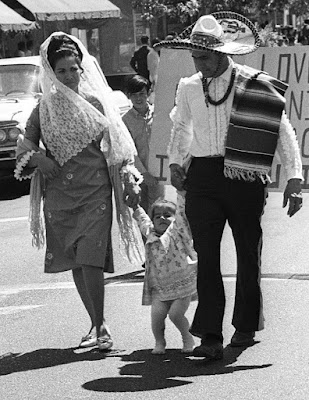

The Tijerinas' 2 and a half-year old daughter Isabel swings between them during the march in downtown Albuquerque.

The Tijerinas' 2 and a half-year old daughter Isabel swings between them during the march in downtown Albuquerque.

Tijerina family members ride on a jeep driven by son Danny.

Tijerina family members ride on a jeep driven by son Danny.

Albuquerque Police Traffic Unit officer blocked traffic at 5th street and Central Avenue downtown for the parade.

Albuquerque Police Traffic Unit officer blocked traffic at 5th street and Central Avenue downtown for the parade.

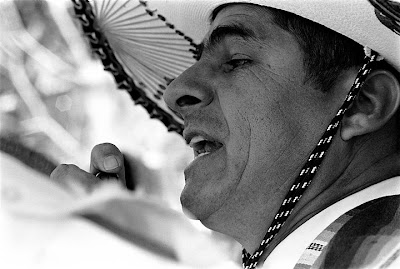

Tijerina spoke to the marchers at the Old Town gazebo then danced with Patsy.

Tijerina spoke to the marchers at the Old Town gazebo then danced with Patsy.

I met Tijerina at the Alianza headquarters and he drove north through Bernalillo towards Rio Arriba County, N.M.

Traveling with Tijerina was his wife, Patsy, their daughter, Isabel, Wilfred Sedillo and Frankie Archibeque.

Tijerina stopped at a gas station and general store in Cuba. He and Patsy did some shopping for food and I took a picture of Isabel who had picked out a large bag of peanuts that she had taken to the counter where the register was.

Tijerina stopped at a gas station and general store in Cuba. He and Patsy did some shopping for food and I took a picture of Isabel who had picked out a large bag of peanuts that she had taken to the counter where the register was.

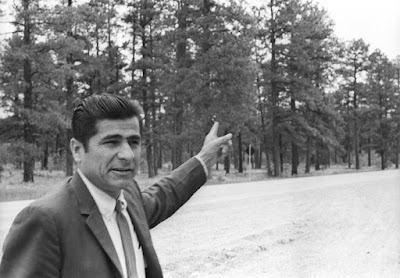

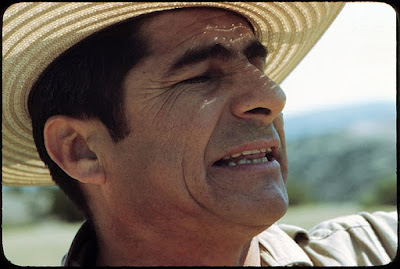

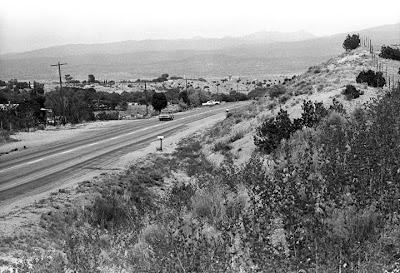

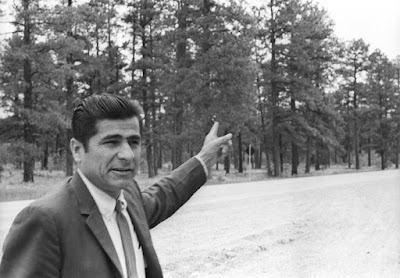

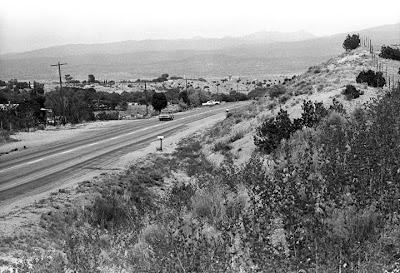

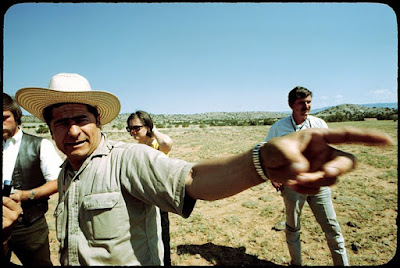

Tijerina stopped at the edge of the highway along State Road 96 between Regina and Gallina to get out of the car to stretch.

He explained how the area was one of the Spanish land grants, called the Free City-State of San Joaquin, established by King Juan Carlos IV of Spain in 1806.

He explained how the area was one of the Spanish land grants, called the Free City-State of San Joaquin, established by King Juan Carlos IV of Spain in 1806.

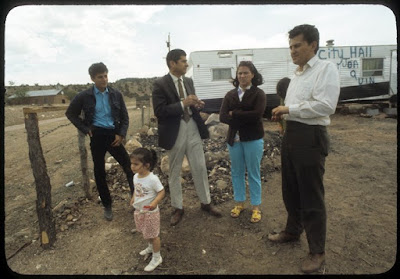

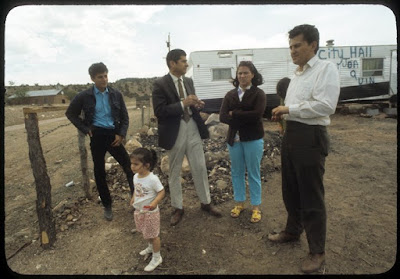

Tijerina stopped at the Alianza's mobile home in Youngsville that had spray-painted on it, “City Hall San Joaquín.” Here are, Tijerina’s son Danny, left, daughter, Isabel, Tijerina, his wife, Patsy, and Frankie Archibeque.

Tijerina stopped at the Alianza's mobile home in Youngsville that had spray-painted on it, “City Hall San Joaquín.” Here are, Tijerina’s son Danny, left, daughter, Isabel, Tijerina, his wife, Patsy, and Frankie Archibeque.

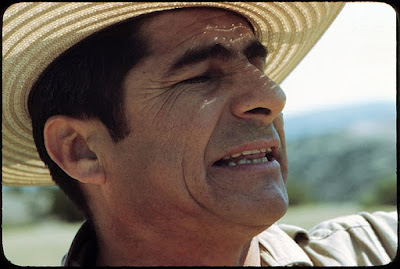

Inside was an old weathered man named Jose Lorenzo Salazar, who was the Mayor of San Joaquín del Río de Chama or the Free City-State of San Joaquin. Tijerina, Wilfredo Sedillo, right, and Mayor Salazar had a conversation in Spanish.

Inside was an old weathered man named Jose Lorenzo Salazar, who was the Mayor of San Joaquín del Río de Chama or the Free City-State of San Joaquin. Tijerina, Wilfredo Sedillo, right, and Mayor Salazar had a conversation in Spanish.

As he watches a New Mexico State Police cruiser pass through Youngsville, Tijerina speaks with Carol Watson and Archibeque, left.

As he watches a New Mexico State Police cruiser pass through Youngsville, Tijerina speaks with Carol Watson and Archibeque, left.

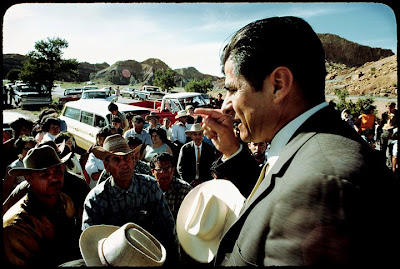

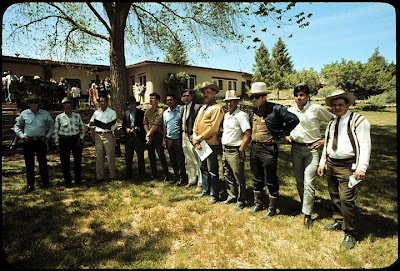

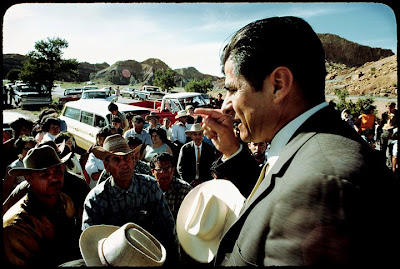

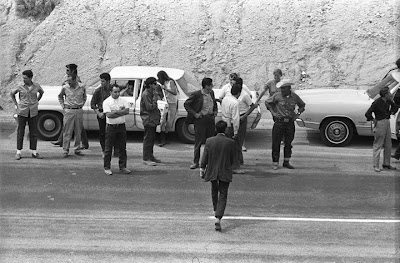

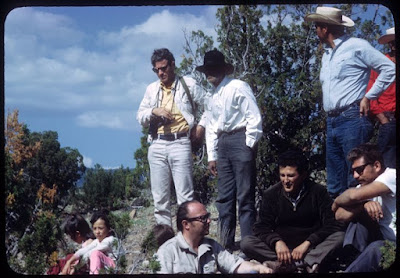

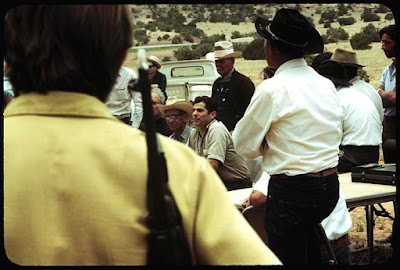

Tijerina drove around Abiquiu Reservoir towards Ghost Ranch and stopped at a roadside rest area on US 84. He met with a group of about 60 Alianza members speaking about the plans for the meeting with the New Mexico synod of the United Presbyterian Church.

Tijerina drove around Abiquiu Reservoir towards Ghost Ranch and stopped at a roadside rest area on US 84. He met with a group of about 60 Alianza members speaking about the plans for the meeting with the New Mexico synod of the United Presbyterian Church.

The Synod of United Presbyterian Church at a meeting in San Antonio earlier in the year had voted to return some land that it had acquired in a land swap with the Forest Service at its Ghost Ranch facility west of Abiquiu. The land was identified as having been the Piedra Lumbre land grant. Grant heirs insisted that the Alianza be involved in the transfer.

The Synod invited Tijerina and Alianza members to discuss the planned return of the land.

The Synod invited Tijerina and Alianza members to discuss the planned return of the land.

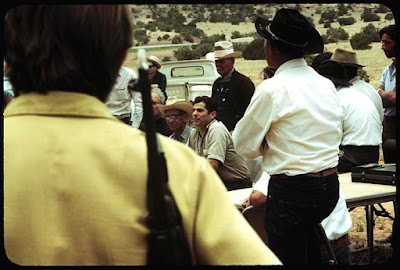

The Alianza group drove to Ghost Ranch where the Presbyterian Synod was meeting.

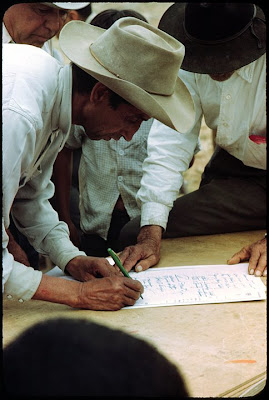

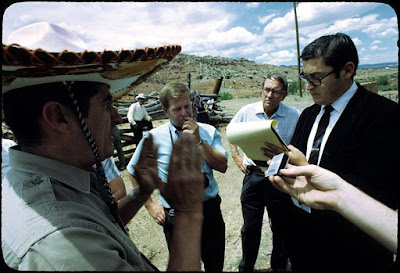

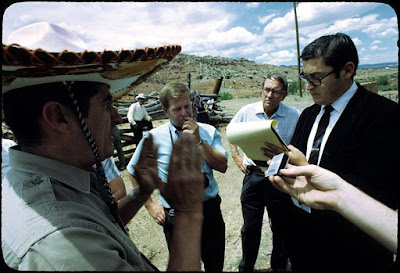

Tijerina, second from left, reviews with Alianza leaders a handout from the Director of the Ghost Ranch Conference Center James Hall. The United Presbyterian Church's position regarding four points:

Tijerina, second from left, reviews with Alianza leaders a handout from the Director of the Ghost Ranch Conference Center James Hall. The United Presbyterian Church's position regarding four points:

The handout went on:

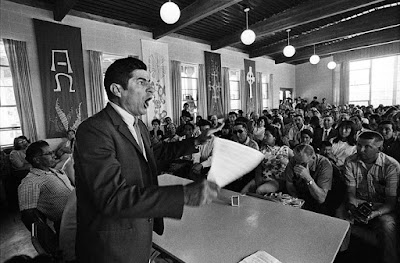

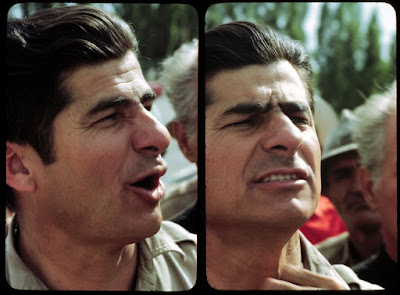

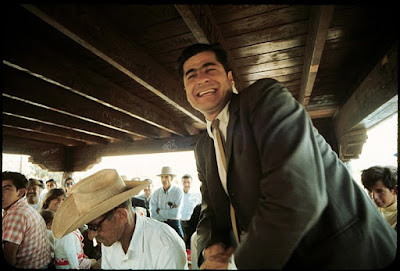

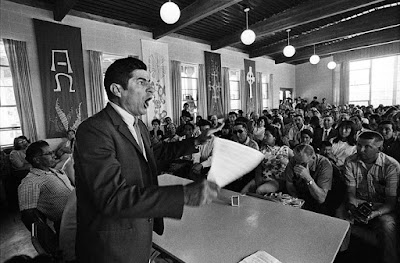

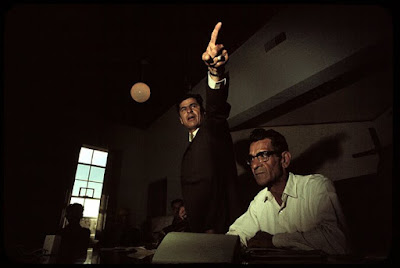

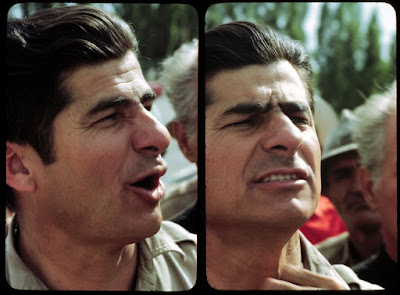

Tijerina responded to the handout forcefully when speaking before the gathering of United Presbyterian Church and Alianza members.

Tijerina responded to the handout forcefully when speaking before the gathering of United Presbyterian Church and Alianza members.

Tijerina speaking before the Synod of United Presbyterian Church delegates at Ghost Ranch with Alianza Vice President Santiago Anaya about plans for the church to exchange land with the Forest Service. Tijerina demanded a role in any such talks.

Tijerina speaking before the Synod of United Presbyterian Church delegates at Ghost Ranch with Alianza Vice President Santiago Anaya about plans for the church to exchange land with the Forest Service. Tijerina demanded a role in any such talks.

After the meeting the Alianza met again at the roadside rest area to talk about what had happened with the Presbyterian Church.

After the meeting the Alianza met again at the roadside rest area to talk about what had happened with the Presbyterian Church.

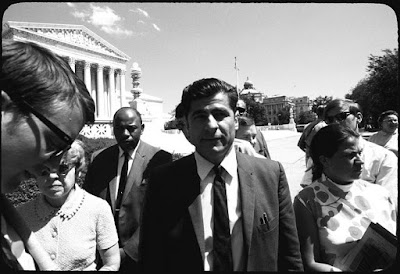

I flew to Washington where Tijerina planned to make a citizen's arrest of Supreme Court Chief Justice designate, Warren Earl Burger.

Upon arriving at Washington National Airport the Tijerinas were met by a man named Aba Sullabum who told me he was the Alianza's representative member in Washington. There were several men (three whom I could determine as police) waiting for Tijerina at the airport. One had a camera and took pictures of people getting off the airplane. There were two others who followed Tijerina. I later found out that the three men were police officers, members of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department's Intelligence Unit. These officers followed the Tijerinas openly everywhere they went. Sullabum accompanied the Tijerinas and myself, followed by our escorts, to the Congressional Hotel on South Capitol Hill. Aba Sullabum gave me the name and phone number of Julius W. Hobson (1919-1977) in case there was any problem. I believe Hobson to have been a Washington attorney who would later become prominent in local District of Columbia politics.

In Washington, the local radio and television news was about the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing for Supreme Court Chief Justice designate Warren Burger. The news report stated that the hearing was expected to be relatively easy for Burger, but there was a possibility of controversy due to Tijerina's stated effort to arrest Burger.

Lyle Denniston, a Writer for "The Evening Star" newspaper, met Tijerina and his wife, Patsy in the hotel lobby asking to follow along with them during the day.

Armed with a legal textbook on "The Laws of Arrest" by Alexander, the Tijerinas set off for the Senate Office building to find the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing room, so he would know where the hearing would be held. He found the hearing room locked.

The Tijerinas, accompanied by the Evening Star reporter Denniston went, by taxi, to the Mayors Office, to ask for him and other city officials to assist in making the citizen's arrest of Burger.

The Tijerinas, accompanied by the Evening Star reporter Denniston went, by taxi, to the Mayors Office, to ask for him and other city officials to assist in making the citizen's arrest of Burger.

The Mayor was not available, so he met with the Assistant Mayor a man named Sullivan who was asked to help in making the arrest.

The Mayor was not available, so he met with the Assistant Mayor a man named Sullivan who was asked to help in making the arrest.

The Assistant Mayor said he would not help, suggesting that the request should be directed towards the police. Tijerina went to the front of the District Building to get a taxi. The driver was told that he wanted to be taken to the Police Department, the building where the Chief's office was located. The cab driver said he was not sure exactly where the building was and left his cab walking back to a car parked behind his cab and asked a plainclothes police officer if the Chief's office was located in the main building of the Police Department.

The Assistant Mayor said he would not help, suggesting that the request should be directed towards the police. Tijerina went to the front of the District Building to get a taxi. The driver was told that he wanted to be taken to the Police Department, the building where the Chief's office was located. The cab driver said he was not sure exactly where the building was and left his cab walking back to a car parked behind his cab and asked a plainclothes police officer if the Chief's office was located in the main building of the Police Department.

Tijerina sought out Chief John Layton of the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, who was not available. He met with an Assistant Chief. Tijerina showed him a copy of the citizen's arrest warrant for Burger and asked for help in making the citizen's arrest. The Assistant Chief looked at the warrant and declined to assist because the warrant did not order him, or any other law enforcement officer to make an arrest, nor did it have a judge's signature. The Assistant Chief did not question the right of a citizen to make an arrest, and though he did not think the scenario that Tijerina laid out for arresting Judge Burger was one in which a citizen could legally make an arrest, he did not deny Tijerina's right to try. The Assistant Chief suggested that Tijerina pursue his efforts through the court system rather than trying to arrest Burger himself.

The Tijerinas returned to the Senate Office building and the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing room where there was a line about 15 people long.

The Tijerinas returned to the Senate Office building and the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing room where there was a line about 15 people long.

Three rather large United States Capitol Police officers barred the door. Press photographers were being allowed into the room. I was denied access to the hearing because I did not have a Senate Press Pass. One of the officers at the door told me I could get a pass at the Senate Press Gallery. I thanked him and began to leave to get the pass. The officer asked if I wanted directions. I declined, knowing where the Press Gallery office was in the Capitol building and then sensed that he was trying to misdirect me. Having lived in the Washington area, several years before, I had spent a good deal of time wandering about the Capitol exploring the buildings. I knew there was a basement subway system that connected the various Senate Office buildings with the Capitol.

Three rather large United States Capitol Police officers barred the door. Press photographers were being allowed into the room. I was denied access to the hearing because I did not have a Senate Press Pass. One of the officers at the door told me I could get a pass at the Senate Press Gallery. I thanked him and began to leave to get the pass. The officer asked if I wanted directions. I declined, knowing where the Press Gallery office was in the Capitol building and then sensed that he was trying to misdirect me. Having lived in the Washington area, several years before, I had spent a good deal of time wandering about the Capitol exploring the buildings. I knew there was a basement subway system that connected the various Senate Office buildings with the Capitol.

I went to the basement subway station just as one of the cars was arriving. I approached the car as it stopped and rushed it as the door opened. However, in my haste, the occupant did not have a chance to exit and I bumped into him as he stepped from the car. I stepped back, excused myself to a rather large man, well over six feet tall, over 200 pounds, with pure white hair and dressed in a black suit. As I stepped back, I realized that there were several other large men with him. They were also dressed in suits, but they were not made of the same quality material as the first man's suit. I realized that these men were security. I could not tell if they were City police, or Supreme Court police, Capitol police, or United States Marshals, or some other Federal Agents and it didn't matter. They were clearly describable as universally cops. I then recognized that this was the entourage of Warren Burger. I had bumped into the judge.

I had a copy of Tijerina's citizen's arrest warrant in my inner jacket pocket and for a fleeting moment thought I could lay the warrant on him. The moment passed very quickly as I thought: it was Tijerina's warrant, I was there to photograph his actions not to become part of the story and looking at these men with Burger, I thought somewhere in the United States, contrary to all the beliefs I had, there was a dungeon and if I tried to confront this man and touch him with a piece of paper I would have found myself in that dungeon. Burger did not say anything to me, his expression did not change and he walked stone faced quickly through the station's doorway and out of sight.

I rode the subway car to the Capitol, took the elevator up to the Senate Gallery level and found the Press Photographers Gallery. I explained my circumstances and was issued a visitor's press photographer's card good for three days.

I hurried back to the Judiciary Committee hearing room and arrived just as the press photographers were being escorted from the room. The police officer recognized my credentials and with a big grin said that the photo opportunity was over. I was able to see into the room and saw that it was a very small hearing room in comparison with other hearing rooms I had seen before. There was the dais at the front of the room, then the witness table and about four rows of about 10 or 15 chairs for a total of maybe 40 to 50 seats. Tijerina was still standing in line with 10 or 15 people ahead of him.

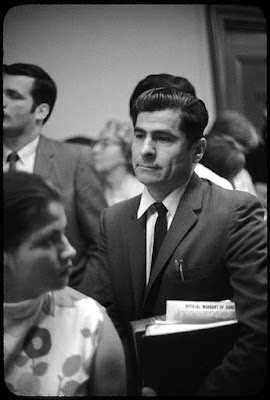

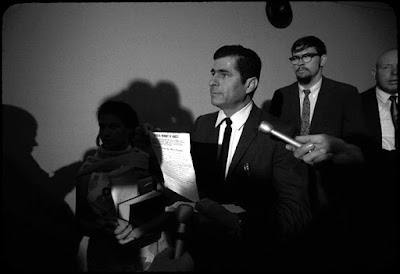

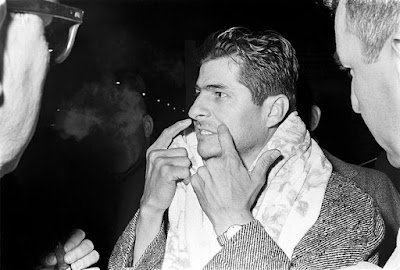

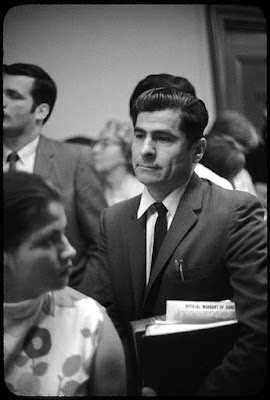

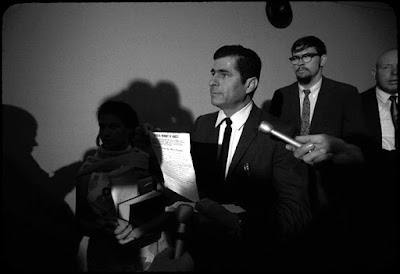

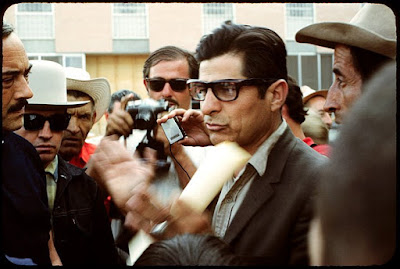

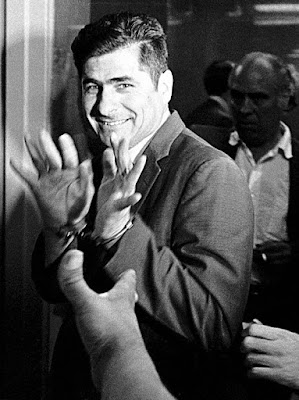

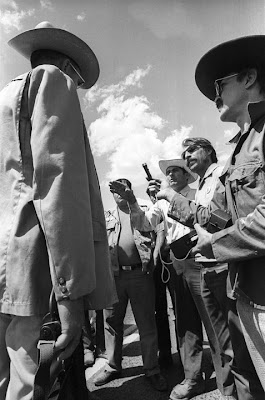

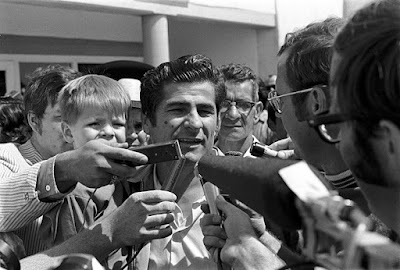

Once the press photographers were out of the hearing room their attention turned to Tijerina who showed them a copy of his warrant and then read it.

Once the press photographers were out of the hearing room their attention turned to Tijerina who showed them a copy of his warrant and then read it.

Several reporters and correspondents interviewed Tijerina on his planed citizen's arrest of Burger at the hearing.

Several reporters and correspondents interviewed Tijerina on his planed citizen's arrest of Burger at the hearing.

The hearing lasted about an hour and forty minutes. I saw one of the men, who had been at the airport and had been following Tijerina earlier in the day. I had seen him in the car when the taxi driver had asked for directions to the police station from the District building; he was now standing in the hall across from the line of people trying to get into the hearing room. I approached this man introducing myself as a photographer for the Albuquerque News and asked him who he was. He told me his name was Sergeant Torres. He was the head of the Intelligence Unit of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police. We talked for a while. He knew Tijerina from the events of the 1968 Poor Peoples March on Washington and activities at "Resurrection City." Tijerina had led a symbolic "Raid" on the Supreme Court building. I asked him if he had met Tijerina? He had not. I told him he might like to meet him; that Tijerina was actually very approachable and because of their mutual Hispanic heritage they might find something in common. At a later time during the day Sgt. Torres and Tijerina did talk.

Tijerina was unable to get into the hearing room and when the meeting was over Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a Republican from Illinois, came into the hallway to talk to the press.

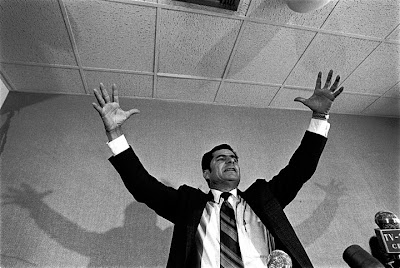

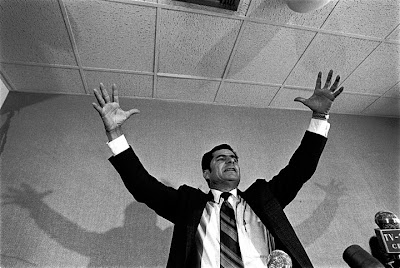

Tijerina was told that Burger had been taken out the back door and had already left the building. Tijerina spoke before the stand of microphones, before Senator Dirksen could, saying, "...then he (Burger) was a fugitive. But, I will be on his tail."

Tijerina was told that Burger had been taken out the back door and had already left the building. Tijerina spoke before the stand of microphones, before Senator Dirksen could, saying, "...then he (Burger) was a fugitive. But, I will be on his tail."

Dirksen waited for Tijerina to finish and then asked the assembled press if they were done with their distinguished friend.

Dirksen waited for Tijerina to finish and then asked the assembled press if they were done with their distinguished friend.

Judge Burger impressed the Committee, Dirksen stated, and they had voted a recommendation to the full Senate and was sure that his confirmation would be swift.

Judge Burger impressed the Committee, Dirksen stated, and they had voted a recommendation to the full Senate and was sure that his confirmation would be swift.

Tijerina was close to Dircksen and expressed his concern that the judge had been taken in and out of the hearing room through the back door "like a thief in the night." The statement angered Senator Dirksen who confronted it. Tijerina and Dircksen had a short discussion ending when Dircksen calls Tijerina's attempt to arrest Burger as being "Totally ridiculous." Dircksen died three months after this encounter at the age of 76.

Tijerina was close to Dircksen and expressed his concern that the judge had been taken in and out of the hearing room through the back door "like a thief in the night." The statement angered Senator Dirksen who confronted it. Tijerina and Dircksen had a short discussion ending when Dircksen calls Tijerina's attempt to arrest Burger as being "Totally ridiculous." Dircksen died three months after this encounter at the age of 76.

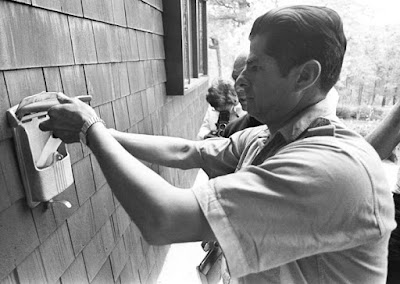

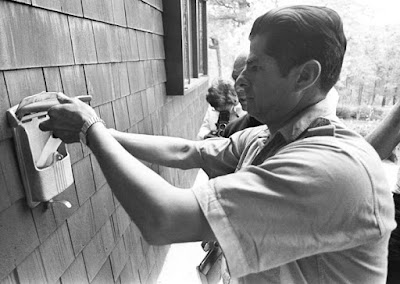

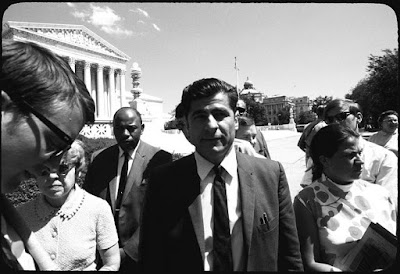

Tijerina was somewhat dejected as he returned to the Congressional Hotel to get lunch. As he passed in front of the Capitol building he looked up at the statute of Freedom atop the dome and said that it was an Indo-Hispano because the statue wears a feathered headdress. The comment made him raise his head and moments later he stated he would pursue Burger. Tijerina entered the House office building, got some scotch tape from a Congressman's office so he could tape a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant on the front door of the Supreme Court. Tijerina said it was like Martin Luther did with his 95 thesis on the door of the German Cathedral.

Tijerina was somewhat dejected as he returned to the Congressional Hotel to get lunch. As he passed in front of the Capitol building he looked up at the statute of Freedom atop the dome and said that it was an Indo-Hispano because the statue wears a feathered headdress. The comment made him raise his head and moments later he stated he would pursue Burger. Tijerina entered the House office building, got some scotch tape from a Congressman's office so he could tape a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant on the front door of the Supreme Court. Tijerina said it was like Martin Luther did with his 95 thesis on the door of the German Cathedral.

After a quick lunch, I met the Tijerinas at the hotel desk where Reies was on the phone checking the schedule for an airplane home, while Patsy was thumbing through a rack of tourist brochures selecting several after reading them.

Tijerina went to the front of the Supreme Court where he met a few members of the press and a TV news crew where he made another statement about Burger having been secreted by the Senate to avoid facing justice. He said he would tape his warrant on the front door of the Supreme Court building. He all the while was being watched closely by a single Supreme Court Police Sergeant.

Tijerina went to the front of the Supreme Court where he met a few members of the press and a TV news crew where he made another statement about Burger having been secreted by the Senate to avoid facing justice. He said he would tape his warrant on the front door of the Supreme Court building. He all the while was being watched closely by a single Supreme Court Police Sergeant.

Tijerina showed the warrant to the officer and asked for his assistance.

Tijerina showed the warrant to the officer and asked for his assistance.

The officer escorted Tijerina inside the front of the building, under the main steps where he and Patsy were taken to the clerk's office. I was barred from taking photographs in the clerk's office.

The officer escorted Tijerina inside the front of the building, under the main steps where he and Patsy were taken to the clerk's office. I was barred from taking photographs in the clerk's office.

Tijerina left a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant with Clerk of the Supreme Court John Davis. Davis recorded that he received it, giving Tijerina a receipt for the warrant.

Tijerina left a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant with Clerk of the Supreme Court John Davis. Davis recorded that he received it, giving Tijerina a receipt for the warrant.

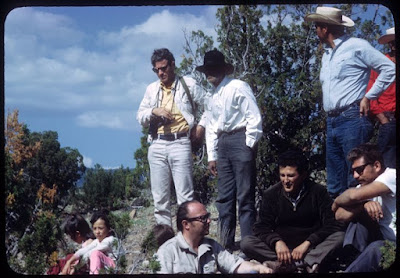

On the way to find Cargo, Tijerina, left, and lawyer Bill Hggs react to the radio news report that the Governor had been moved and Tijerina returned to the Abiquiu site to reformulate their day's plans.

On the way to find Cargo, Tijerina, left, and lawyer Bill Hggs react to the radio news report that the Governor had been moved and Tijerina returned to the Abiquiu site to reformulate their day's plans.

Tijerina changed plans for making a citizen's arrest of the governor to trying to arrest the heads of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories.

Tijerina changed plans for making a citizen's arrest of the governor to trying to arrest the heads of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories.

The matter was put to a vote.

The matter was put to a vote.

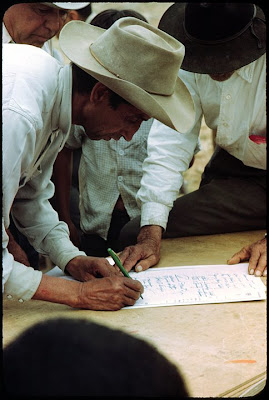

Juan Roybal signs his to the register of the vote as Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant's Mayor Salazar holds the paper down from blowing in the wind.

Juan Roybal signs his to the register of the vote as Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant's Mayor Salazar holds the paper down from blowing in the wind.

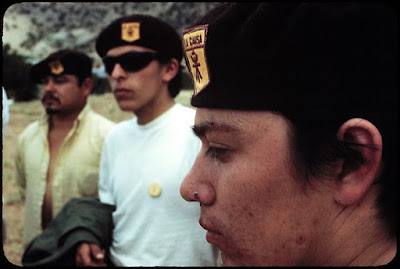

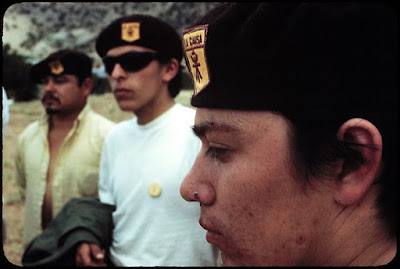

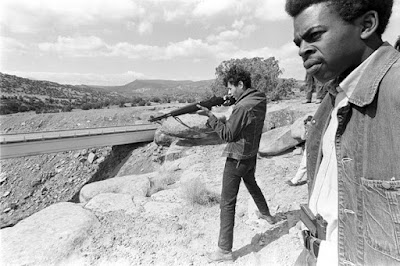

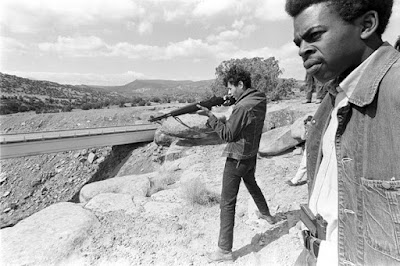

Brown Beret members watched the proceedings.

Brown Beret members watched the proceedings.

Before the caravan set off for Los Alamos, Juan Roybal sang Spanish songs accompanied by a guitarist to entertain the Alianza crowd.

Before the caravan set off for Los Alamos, Juan Roybal sang Spanish songs accompanied by a guitarist to entertain the Alianza crowd.

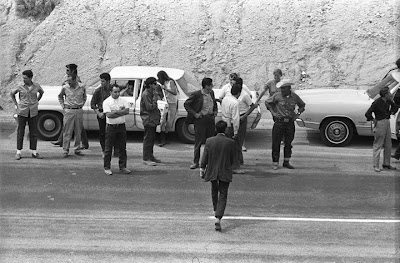

On the way to Los Alamos, Tijerina's vehicle experienced some minor problem and he pulled to the side of the road. Those following also pulled over.

On the way to Los Alamos, Tijerina's vehicle experienced some minor problem and he pulled to the side of the road. Those following also pulled over.

The State Police officer following the caravan also pulled over.

The State Police officer following the caravan also pulled over.

Tijerina did not know at the time know that Norris Bradbury was the head of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories, but found out by going to the Laboratories museum at the headquarters.

Tijerina did not know at the time know that Norris Bradbury was the head of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories, but found out by going to the Laboratories museum at the headquarters.

Tijerina was unable to locate Bradbury, who was playing golf, but left a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant in Bradbury's mailbox, at his home.

Tijerina was unable to locate Bradbury, who was playing golf, but left a copy of his citizen's arrest warrant in Bradbury's mailbox, at his home.

Tijerina spoke to his followers in Los Alamos about the day's activities.

It was part of his routine when he engaged in his public acts; he held a pre-event meeting, if the press was there, all the better, he would hold his event, often times an expression of civil disobedience, followed by a post-event meeting to explain what he had done and to claim a moral victory against the oppressors of the people he represented. No one knew that this would be one of the last such activities he would hold as his militancy was coming to an end. In his autobiography, in describing the week he wrote:

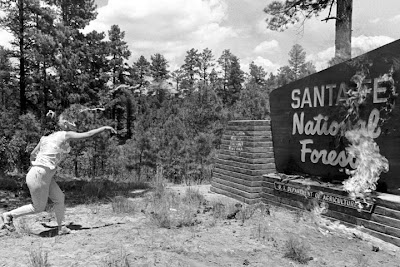

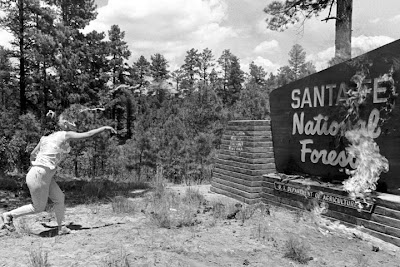

Patsy Tijerina announced her intention to burn a National Forest Service sign.

Patsy Tijerina announced her intention to burn a National Forest Service sign.

In the afternoon a caravan proceeded west to the Santa Fe National Forest sign near Gallina.

In the afternoon a caravan proceeded west to the Santa Fe National Forest sign near Gallina.

Tijerina told me I could not accompany them for, "legal reasons." I rode in a vehicle that followed the Tijerina's car in the caravan.

Patsy Tijerina was placing fallen pine sticks and newspaper under the sign by the time I arrived. The National Forest Service sign was made of a brick base with three iron "I" beams that raised from the base and had two panels of wood attached to them by bolts.

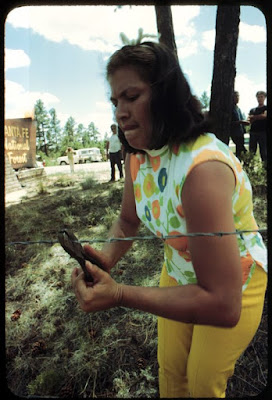

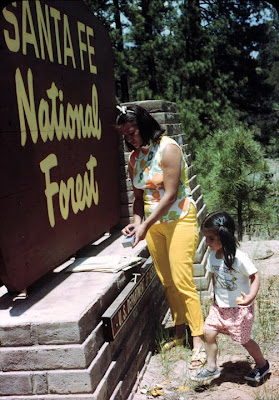

Isabel Tijerina followed her mother.

Isabel Tijerina followed her mother.

Patsy poured gasoline from a Coca-Cola bottle over the newspapers and lit the National Forest Service sign that flared then began to burn. The flames worked their way up the inside of the two panels that created a chimney effect.

Patsy poured gasoline from a Coca-Cola bottle over the newspapers and lit the National Forest Service sign that flared then began to burn. The flames worked their way up the inside of the two panels that created a chimney effect.

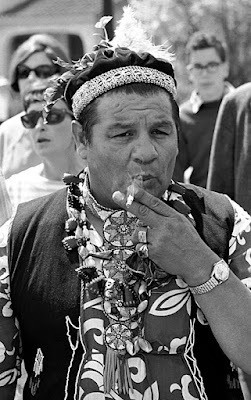

The outside of the sign showed little indication of fire. The visual image was not dramatic. Ramón Tijerina approached and Patsy assisted him in getting a burning stick, then proceeded to light his cigar for him. She stoked the coals to try to get the outer part of the sign to ignite, but it wouldn't.

The outside of the sign showed little indication of fire. The visual image was not dramatic. Ramón Tijerina approached and Patsy assisted him in getting a burning stick, then proceeded to light his cigar for him. She stoked the coals to try to get the outer part of the sign to ignite, but it wouldn't.

A man brought Patsy a Coca-Cola bottle filled with gasoline that she threw at the sign. The bottle hit the sign and ignited, falling to the base breaking, and then flared up. The outside of the sign still did not catch fire.

A man brought Patsy a Coca-Cola bottle filled with gasoline that she threw at the sign. The bottle hit the sign and ignited, falling to the base breaking, and then flared up. The outside of the sign still did not catch fire.

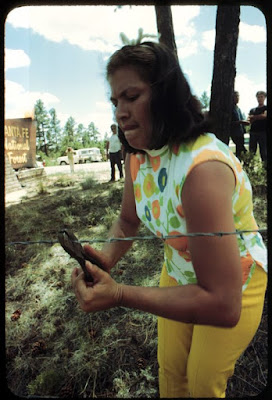

Patsy then took a pair of pliers and cut about 35 yards of fencing. The sign was consumed from the inside until flames broke through and the panels fell off their bolts.

Patsy then took a pair of pliers and cut about 35 yards of fencing. The sign was consumed from the inside until flames broke through and the panels fell off their bolts.

Patsy found a part of the sign, a wooden replica of the U. S. Forest Service badge, which had previously been torn from or had fallen off the brick piling and she threw it onto the fallen panel.

Patsy found a part of the sign, a wooden replica of the U. S. Forest Service badge, which had previously been torn from or had fallen off the brick piling and she threw it onto the fallen panel.

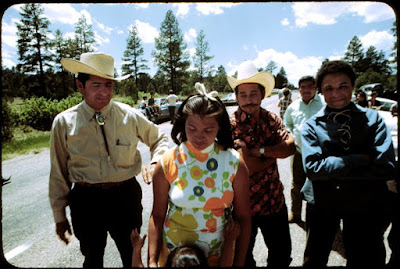

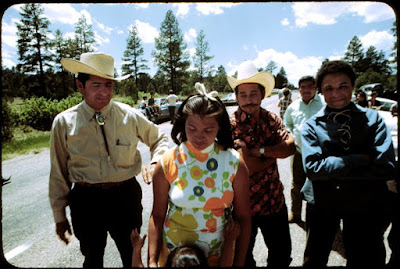

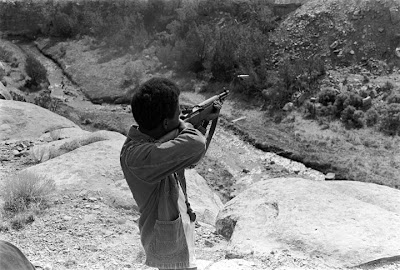

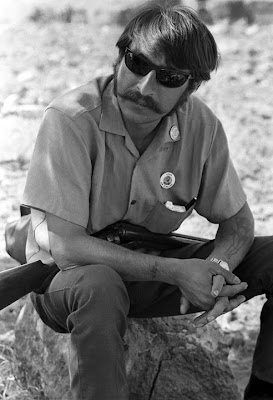

Jose "Duke" Aragon, far right, a man who acted as one of Tijerina's bodyguards, took out a small .22 cal. pistol that he always wore in a holster on his belt and fired it into the air, then Reies' brother, Ramón Tijerina, right, took the pistol and also fired it into the air. Reies Tijerina at the edge of the road, center, with his son Danny, left, watch as Samuel "Hap" Stewart, in white and wearing sunglasses photographed the event.

Jose "Duke" Aragon, far right, a man who acted as one of Tijerina's bodyguards, took out a small .22 cal. pistol that he always wore in a holster on his belt and fired it into the air, then Reies' brother, Ramón Tijerina, right, took the pistol and also fired it into the air. Reies Tijerina at the edge of the road, center, with his son Danny, left, watch as Samuel "Hap" Stewart, in white and wearing sunglasses photographed the event.

The photograph also shows how close Tijerina came to the burning sign, about 40 feet. He would testify that he was a reluctant protester.

Reies Tijerina, left, stood back during the sign burning, then drove his wife, Patsy, center, towards Coyote. Tijerina invited me to ride in his car on the way back to the campsite. Also in the car were: a member of the Brown Berets, a man I took to be a member of the Alianzia, and SNCC's National Program Secretary Hutchings, right.

Reies Tijerina, left, stood back during the sign burning, then drove his wife, Patsy, center, towards Coyote. Tijerina invited me to ride in his car on the way back to the campsite. Also in the car were: a member of the Brown Berets, a man I took to be a member of the Alianzia, and SNCC's National Program Secretary Hutchings, right.

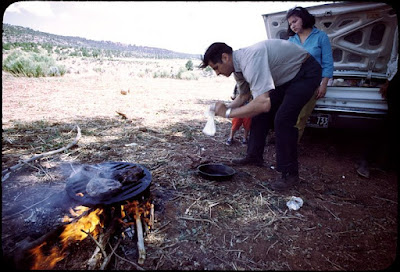

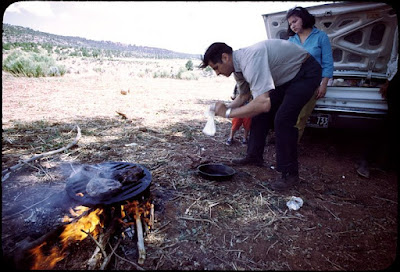

Tijerina stopped the car at the side of the road where there was a downed tree and instructed Patsy to gather firewood.

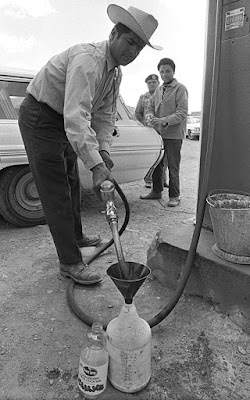

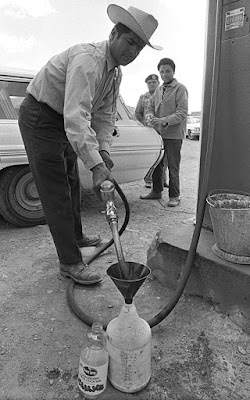

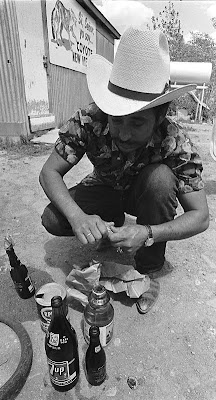

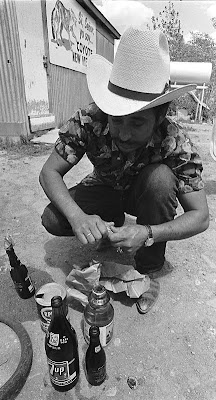

Tijerina stopped the car again at a Mobil gas station that was part of the general store in Coyote. He purchased gas for the car; then filled a plastic Clorox bottle with gas.

Tijerina stopped the car again at a Mobil gas station that was part of the general store in Coyote. He purchased gas for the car; then filled a plastic Clorox bottle with gas.

The gas was distributed into several glass containers: a pint cranberry juice bottle, a pint 7-up bottle and a couple of 12 ounce, 7-up bottles.

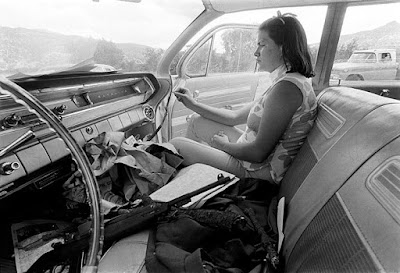

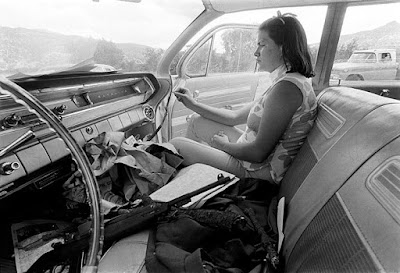

Patsy stayed in the car and someone brought her a bottle of orange soda pop. She had a wooden "strike anywhere" match that she played with in her right hand. On the front seat of the Pontiac station wagon was a pile of newspapers, the wood she had collected from the downed tree and two firearms. There was a Walther P.38 semi automatic pistol and a .30-06 M-1 Carbine rifle. Both guns were on the driver’s side of the front seat.

Patsy stayed in the car and someone brought her a bottle of orange soda pop. She had a wooden "strike anywhere" match that she played with in her right hand. On the front seat of the Pontiac station wagon was a pile of newspapers, the wood she had collected from the downed tree and two firearms. There was a Walther P.38 semi automatic pistol and a .30-06 M-1 Carbine rifle. Both guns were on the driver’s side of the front seat.

Tijerina drove to the entrance of the National Forest Service's Coyote Ranger Station, followed by the caravan. Reyes Jr., his wife, right, Kerim Hamarat, with his dog, and several of the teenaged boys traveling with the caravan moved to the south side of the sign to watch. Patsy took the newspapers, placed them under the sign along with the firewood she had gathered. She put the newspapers and the wood under and between the two parts of the sign.

She poured gas from the glass pint cranberry juice bottle and pint 7-up bottles that had earlier come from the gas station. She ignited the newspaper to burn the Coyote Ranger Station, Santa Fe Forest sign.

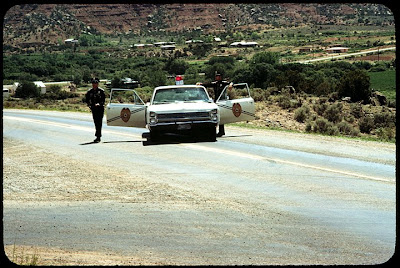

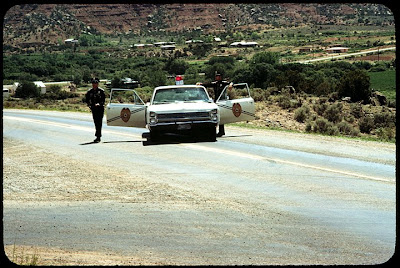

Just as Patsy lit the sign, two New Mexico State Police cars approached at high rates of speed from opposite directions, with red lights rotating, passing each other in front of the sign.

Just as Patsy lit the sign, two New Mexico State Police cars approached at high rates of speed from opposite directions, with red lights rotating, passing each other in front of the sign.

Patsy, accompanied by Reyes Jr. walks away from the burning sign. Ramon Tijerina, in white shirt watches as State Police officers arrive.

Patsy, accompanied by Reyes Jr. walks away from the burning sign. Ramon Tijerina, in white shirt watches as State Police officers arrive.

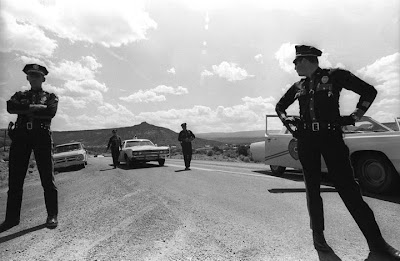

Officers braked to a stop turning across the oncoming traffic lane blocking the roadway.

Officers braked to a stop turning across the oncoming traffic lane blocking the roadway.

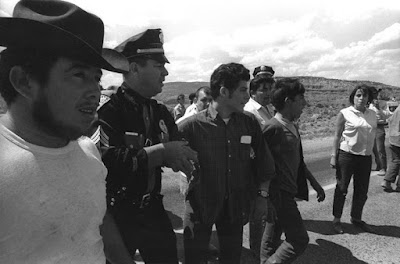

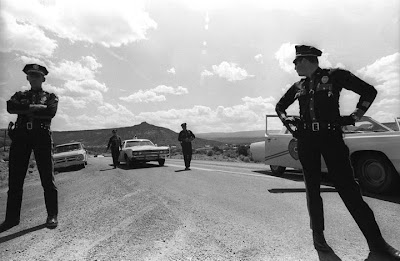

Several other State Police vehicles, up to maybe eight approached and parked on or next to the road. Uniformed New Mexico State Police officers included: Sergeant Joe Tarazon Jr., Robert Gonzales, Mike Montoya, Joe Mascarenas, and Jerome Jones. There were also at least two plainclothes officers: Detectives Robert Gilliland and Jack Johnson.

Several other State Police vehicles, up to maybe eight approached and parked on or next to the road. Uniformed New Mexico State Police officers included: Sergeant Joe Tarazon Jr., Robert Gonzales, Mike Montoya, Joe Mascarenas, and Jerome Jones. There were also at least two plainclothes officers: Detectives Robert Gilliland and Jack Johnson.

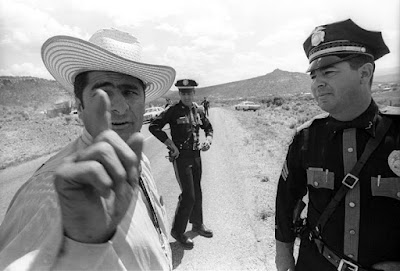

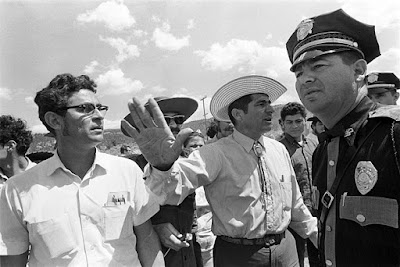

Tijerina spoke with the closest State Police officer identifying Patsy as the person who burned the Gallina and Coyote Forest Service signs. The Sergeant quickly relieved the officer.

Tijerina spoke with the closest State Police officer identifying Patsy as the person who burned the Gallina and Coyote Forest Service signs. The Sergeant quickly relieved the officer.

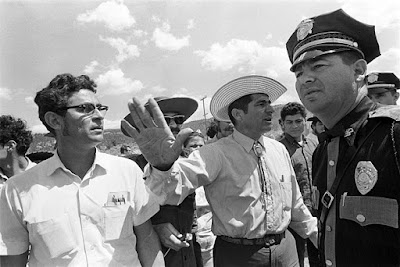

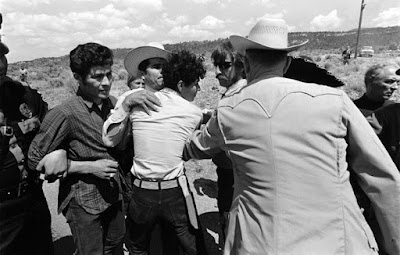

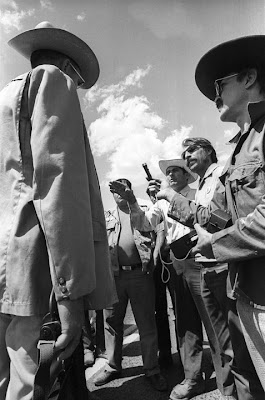

Uniformed New Mexico State Police Sergeant Joe Tarazon, right, National Forest Service Rangers and other law enforcement officers in plain clothes converged on the scene as Danny, left looking out of the picture, brother Ramón, Reies, and son David Hugh, also known as Reies Jr., Tijerina confront the officers.

Uniformed New Mexico State Police Sergeant Joe Tarazon, right, National Forest Service Rangers and other law enforcement officers in plain clothes converged on the scene as Danny, left looking out of the picture, brother Ramón, Reies, and son David Hugh, also known as Reies Jr., Tijerina confront the officers.

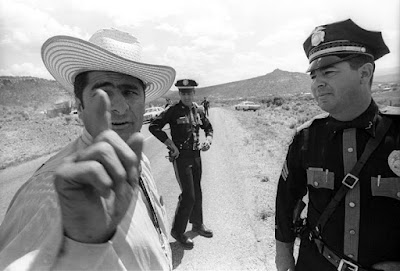

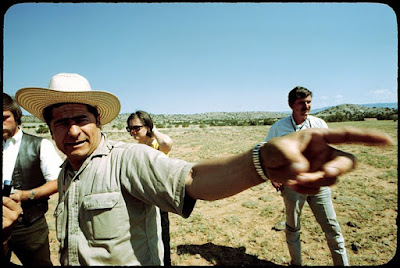

Tijerina points out his wife Patsy to State Police Sgt. Tarazon, right, as the person who burned the signs, in flame in the background.

Tijerina points out his wife Patsy to State Police Sgt. Tarazon, right, as the person who burned the signs, in flame in the background.

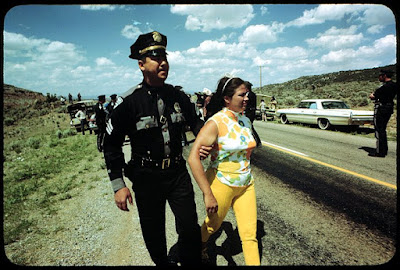

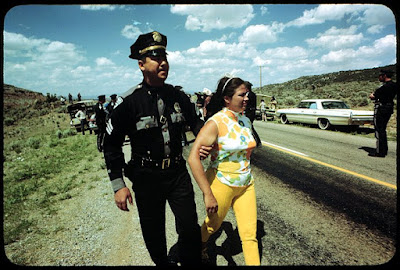

Tarazon arrests Patsy.

Tarazon arrests Patsy.

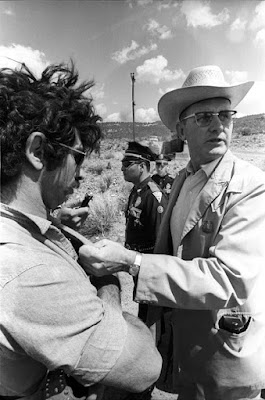

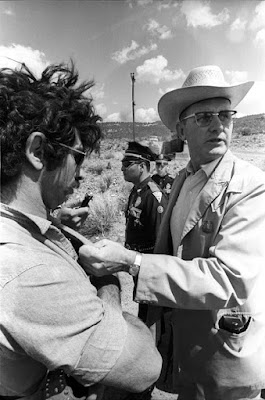

Officers were lead by Chief of the Law Enforcement Branch of the Forest Service for the southwest region James Evans. He approached Tijerina to arrest him but meets Kerim Hamarat who confronts Evans.

Officers were lead by Chief of the Law Enforcement Branch of the Forest Service for the southwest region James Evans. He approached Tijerina to arrest him but meets Kerim Hamarat who confronts Evans.

Hamarat armed himself by taking the spiked collar off his German shepherd dog. Evans arrested Hamarat grabbing him by the front of his vest.

Hamarat armed himself by taking the spiked collar off his German shepherd dog. Evans arrested Hamarat grabbing him by the front of his vest.

State Police Sgt. Tarazon and other State Police officers took Hamarat into custody. Officer Clarence Filip, right, took a hunting knife from Hamarat's belt as Officer Leroy Urioste watches.

State Police Sgt. Tarazon and other State Police officers took Hamarat into custody. Officer Clarence Filip, right, took a hunting knife from Hamarat's belt as Officer Leroy Urioste watches.

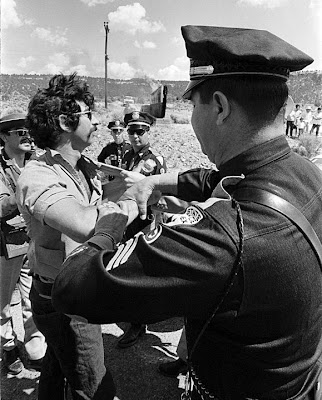

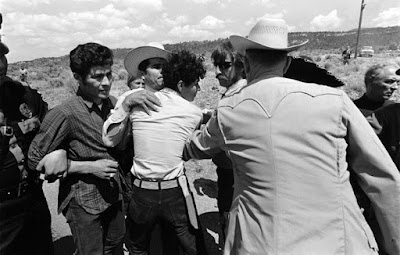

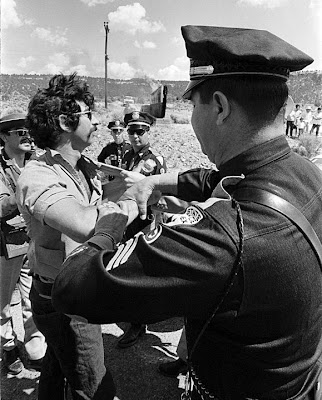

Evans confronted Tijerina who was surrounded closely by about twenty to thirty people including; his two sons, Reyes Hugh and Danny, Reyes Hugh's wife, Kerim Hamarat, Carol Watson, Rudy Trujillo, Wilfredo Sedillo, who was tape recording the event. "Bodyguards," Jose (Duke) Aragon and Juan Roybal are in very close.

Evans told Tijerina he is under arrest. Reies told Evans that as a citizen he was placing him under a "citizens arrest." Evans told Tijerina that because he was already under arrest he could not make a "citizens arrest."

Evans told Tijerina he is under arrest. Reies told Evans that as a citizen he was placing him under a "citizens arrest." Evans told Tijerina that because he was already under arrest he could not make a "citizens arrest."

Reyes Hugh López Tijerina Jr., left, stepped forward and says he is placing Evans under "citizens arrest." Evans tells Reyes Hugh that is also under arrest and turns towards Reies reaching out grabbing him by his belt. At the far left is Carol Watson of New York who would be arrested after she "pinched" Evans' hand trying to get him to release Tijerina. These photographs do not show that act, though they show her close. Former Albuquerque radio reporter, then of a Los Angeles radio station announcer, Alfonso Tafoya, right, holding down his flat topped hat holds his microphone, seen between Evans and the Tijerinas.

Reyes Hugh López Tijerina Jr., left, stepped forward and says he is placing Evans under "citizens arrest." Evans tells Reyes Hugh that is also under arrest and turns towards Reies reaching out grabbing him by his belt. At the far left is Carol Watson of New York who would be arrested after she "pinched" Evans' hand trying to get him to release Tijerina. These photographs do not show that act, though they show her close. Former Albuquerque radio reporter, then of a Los Angeles radio station announcer, Alfonso Tafoya, right, holding down his flat topped hat holds his microphone, seen between Evans and the Tijerinas.

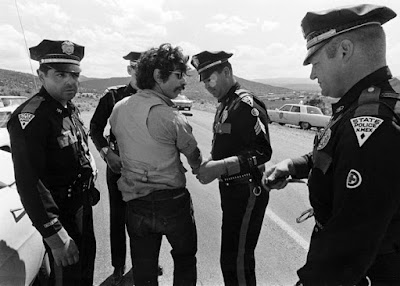

Reies outstretched his arms, placing his hands on the shoulders of his son Danny, left, and on Rudy Trujillo. Trujillo reaches across Evans' chest trying to pull him away from Tijerina.

Reies outstretched his arms, placing his hands on the shoulders of his son Danny, left, and on Rudy Trujillo. Trujillo reaches across Evans' chest trying to pull him away from Tijerina.

Danny wraps his arms around his father and Rudy Trujillo is pulled close into Reies' body. "Bodyguard" Jose "Duke" Aragon gets between Evans and Tijerina as Reies strains to break Evans' grasp. Sgt. Tarazon moves in behind Reies and takes Reyes Hugh into custody. Above Tarazon's left shoulder is plain clothed State Police Officer Jack Johnson with binoculars around his neck and a rifle in his hand.

Danny wraps his arms around his father and Rudy Trujillo is pulled close into Reies' body. "Bodyguard" Jose "Duke" Aragon gets between Evans and Tijerina as Reies strains to break Evans' grasp. Sgt. Tarazon moves in behind Reies and takes Reyes Hugh into custody. Above Tarazon's left shoulder is plain clothed State Police Officer Jack Johnson with binoculars around his neck and a rifle in his hand.

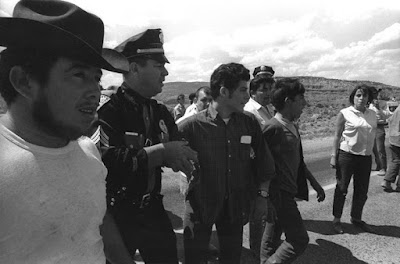

Sgt. Tarazon takes Reyes Hugh by the arm leading him away from the confrontation. Reyes Hugh does not resist as Sgt. Tarazon places a wrist restraint grip to control him.

Sgt. Tarazon takes Reyes Hugh by the arm leading him away from the confrontation. Reyes Hugh does not resist as Sgt. Tarazon places a wrist restraint grip to control him.

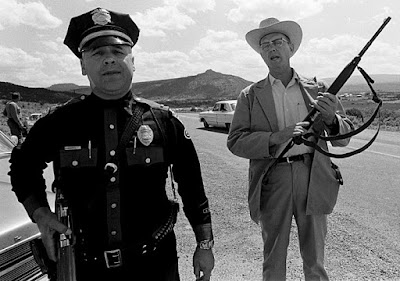

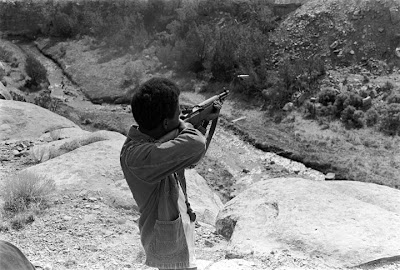

As Tijerina breaks free of Evans' grasp, he "walks hurriedly" according to State Policeman Robert Gilliland's later testimony or runs to his station wagon as the crowd remains still watching Reies. Tijerina retrieves the .30-06 rifle from the front seat of his car, actuates the receiver, waves the weapon from side to side, indicating people should clear a way and then levels the rifle at Evans.

State Police Officer Johnson came off the hill on the other side of Tijerina's car and he: raised the hood of the vehicle, removed the distributor cap, disabling the car. Johnson points his own rifle at Tijerina's head, telling him, "Psst. Reies, you're a dead man."

"Bodyguard" Juan Roybal, left, convinced Tijerina to surrender.

"Bodyguard" Juan Roybal, left, convinced Tijerina to surrender.

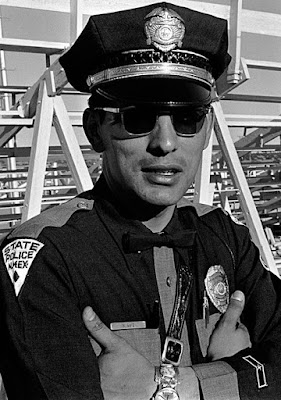

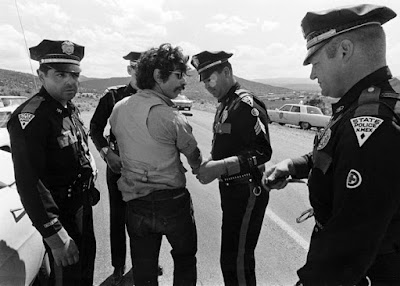

Tijerina waved off the first state policeman who approaches him because he is Anglo and called for a Hispanic Officer Manuel Martinez, to whom he surrenders and is taken into custody.

Tijerina waved off the first state policeman who approaches him because he is Anglo and called for a Hispanic Officer Manuel Martinez, to whom he surrenders and is taken into custody.

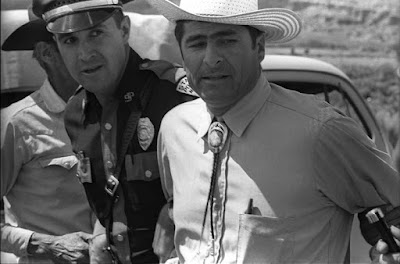

Espanola's State Police District Commander Lieutenant Jose "J.D." Maes arrived on the scene well after the event was over. Armed with a customized gold-plated carbine, Maes consults with Evans.

Espanola's State Police District Commander Lieutenant Jose "J.D." Maes arrived on the scene well after the event was over. Armed with a customized gold-plated carbine, Maes consults with Evans.

Also arrested were: brother Ramón Tijerina, son Reyes Hugh, Carol Watson, Kerim Hamarat, Manuel Rudy, and José Aragón.

Tijerina and Patsy were released on their own recognizance.

After bonding out of jail, Tijerina and some of his follower went to the home of Evens to attempt to serve a citizen's arrest on him.

They were unsuccessful and the United States attorney had Tijernia retaken for violations of conditions of his bond release and held on no bond.

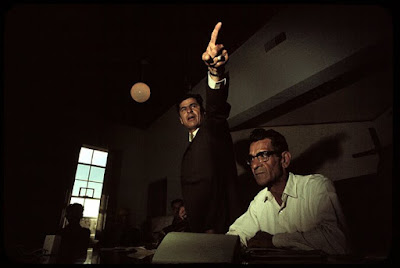

United States District Court Judge Howard Bratton held a bond revocation hearing. The United States Attorney was Victor R. Ortega and his assistant was Michael P. Watkins.

United States District Court Judge Howard Bratton held a bond revocation hearing. The United States Attorney was Victor R. Ortega and his assistant was Michael P. Watkins.

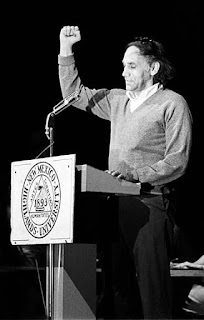

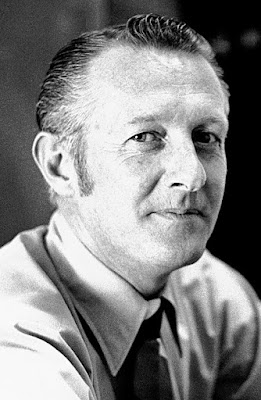

Tijerina's lawyer was American Civil Liberties Union Chief Trial Attorney William Kunstler, seen here during a later speech he gave at New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas.

I was subpoenaed to testify by both the prosecution and defense.

I testified and was on witness stand for two hours. Defense Attorney Kunstler questioned me for about an hour and a half and was stopped by Judge Bratton when he started asking the chemical make up of the film developer.

Bratton, an admitted advanced armature photographer, ruled that I did not have to understand all the chemical properties of the photographic process to be a photographer.

I was not being offered as an expert witness. The only thing I needed to do was testify that the prints offered into evidence clearly depicted what I saw at the time the picture was taken.

Kunstler's main attack was that New Mexico State Police and Forest Service Law Enforcement Chief Evans tried to kill Tijerina on the road in front of the ranger station.

Kunstler focused in on a particular picture of a State Police Officer Martinez, center, for having had his hand resting on his holstered gun. Kunstler tried to get me to testify that the officer was drawing the weapon.

Kunstler focused in on a particular picture of a State Police Officer Martinez, center, for having had his hand resting on his holstered gun. Kunstler tried to get me to testify that the officer was drawing the weapon.

The court presentation print was not large enough for Kunstler to easily discern the location of the officer's hand. Here is a blow up of the Martinez's hand, which is not gripping the butt of the weapon. The restraining strap was not unsnapped. The strap visible is either that of a slapper of a gas billy in a small pocket below and to the right of the right rear pocket. Martinez did not draw his weapon at this point; he might have later when Tijerina brought his M-1 into play.

The court presentation print was not large enough for Kunstler to easily discern the location of the officer's hand. Here is a blow up of the Martinez's hand, which is not gripping the butt of the weapon. The restraining strap was not unsnapped. The strap visible is either that of a slapper of a gas billy in a small pocket below and to the right of the right rear pocket. Martinez did not draw his weapon at this point; he might have later when Tijerina brought his M-1 into play.

Kunstler's activities, including his representation of Tijerina were documented in a Look magazine article entitled "'The blackest white man I know' Civil Rights Lawyer William Knustler is soul brother to radicals of many colors." Playboy magazine would call him a "courtroom freedom fighter."

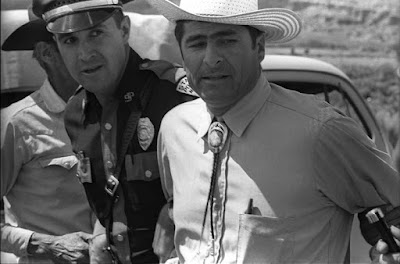

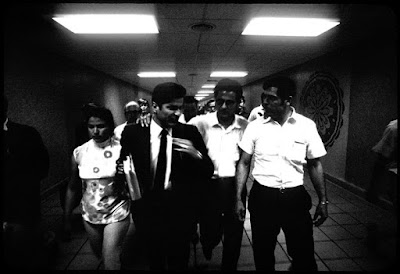

Tijerina with U.S. Marshal for New Mexico Doroteo Robert Baca being moved from Federal court during his bond revocation hearing.

September 22, 1969, Tijerina's trial starts on charges arising from the sign burnings. He faced two counts of aiding abetting his wife Patsy in the destruction of government property and one count of resisting arrest by assaulting a federal law enforcement officer.

September 25, 1969, I testify under direct examination and was on witness stand as the last witness as the government rests.

September 27, 1969, I testify as a rebuttal witness.

Reies Lopez Tijerina was found guilty, convicted on 3 counts in Federal District Court.

In November 1969, Newsweek magazine contacted my father, while I was studying in New York City at the New York Institute of Photography. Newsweek wanted to buy a photograph of Reies Lopez Tijerina to illustrate a story.

In the December 15, 1969, issue of Newsweek, in the Religion section there was an article, "The Almoner's Dilemma," which discussed a rift in the Episcopal church's over giving money to legitimate organizations providing services, as long as they are, "non-violent."

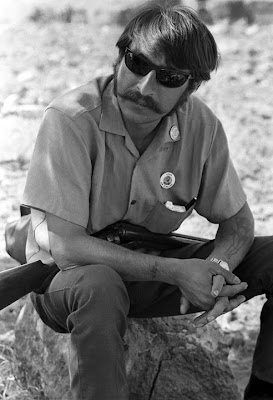

This picture illustrated the article with the caption, "Alianza's Brown Beret: Power, prioity and a Christian position".

This picture illustrated the article with the caption, "Alianza's Brown Beret: Power, prioity and a Christian position".

The Alianza was slated to receive $41,000. New Mexico Bishop Charles J. Kingsolving objected claiming because Tijerina had been convicted in the Echo Amphitheater case that the Alianza was a violent organization.

The screening committee, on the other hand, supports the Alianza's efforts to organize

Tijerina and the Alianza made claims to land grants based on provisions of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hildalgo ending the Mexican-American War. The U.S. Senate struck provisions for land grants from the treaty, however the New Mexico State Constitution addresses treaty provisions for land grants to remain intact as issued by the Spanish crown:

Article II - Bill of RightsThough some grants were issued to individuals, most land grants were made as property of towns comprised of several families and were not to be subdivided, but were to be maintained for future use. A residential area set aside existed and all the other area was to be for a common use, including: irrigation, farming, grazing, and lumbering. Such community grants could not be sold or broken up.

Sec. 5. Rights under Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo preserved.

The rights, privileges and immunities, civil, political and religious guaranteed to the people of New Mexico by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo shall be preserved inviolate.

Despite efforts to resolve land grant claims that, included a series of Federal Court cases heard in 1891, and eventually appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which said the matter, because it was a treaty, a Congressional issue; Congress has never addressed or tried to clarify the issue.

The issue has been kept alive and is repeatedly submitted to Congress, but the bill never makes it through a committee hearing. In the practical sense it is an issue unlikely to be resolved.

In the summer of 1966, Tijerina led a group of followers on a three-day march from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to present Alianza land grant demands to New Mexico Governor Jack Campbell.

In the summer of 1966, Tijerina led a group of followers on a three-day march from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to present Alianza land grant demands to New Mexico Governor Jack Campbell. The Alianza also met with newly elected New Mexico Governor David F. Cargo, seen here during the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970.

The Alianza also met with newly elected New Mexico Governor David F. Cargo, seen here during the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970. On October 22, 1966, the Alianza Federal de Mercedes held a convention at the Echo Amphitheater campground in the Carson National Forest, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. The Alianza claimed the property to be the Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant taken from the people and illegally under the control of the United States.

On October 22, 1966, the Alianza Federal de Mercedes held a convention at the Echo Amphitheater campground in the Carson National Forest, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. The Alianza claimed the property to be the Pueblo San Joaquin del Rio de Chama land grant taken from the people and illegally under the control of the United States.Two U.S. Forest workers tried to collect campground user fees from the group. The land grant’s marshals seized rangers Walter Taylor and Phil Smith and their vehicles.

A "mock" trial was commenced and rangers were convicted of trespass and being a nuisance. They were given suspended sentences and were released. Their trucks were "impounded."

On June 5, 1967, Tijerina led the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid." The purpose was to free some Alianza members from jail who had been arrested at an earlier event. Ironically, the men were freed and had left the courthouse shortly before the jailbreak occurred.

On June 5, 1967, Tijerina led the Tierra Amarilla courthouse "raid." The purpose was to free some Alianza members from jail who had been arrested at an earlier event. Ironically, the men were freed and had left the courthouse shortly before the jailbreak occurred. During the "raid" two law enforcement officers were shot: New Mexico State Police Officer Nick Saiz, seen here at the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970, and Rio Arriba County Jailer Eulogio Salazar. Tijerina was charged with shooting Salazar twice, once in the jaw.

During the "raid" two law enforcement officers were shot: New Mexico State Police Officer Nick Saiz, seen here at the National Spring Republican Governors Conference in Santa Fe, May 1970, and Rio Arriba County Jailer Eulogio Salazar. Tijerina was charged with shooting Salazar twice, once in the jaw.Associated Press Writer Larry Calloway was in the courthouse in a phone booth filing his story to the AP office in Albuquerque when gunfire erupted. Calloway has written at length about his experience; he was kidnapped and held by a couple of the raiders.

Salazar was abducted from in front of his home while opening his gate and was later found murdered in his car. Suspicion immediately turned to Tijerina and the Alianza. The investigation was short lived. Several members of the Alianza were arrested, but all could account for their whereabouts at the time of the murder and no one was charged. A law enforcement official close to the investigation at the time told me some undisclosed Constitutional issue made the case impossible to pursue, though police believe they knew what happened. New Mexico District Judge Joe Angle slapped a gag order on government officials, from the governor on down through law enforcement, to not comment about the case or investigation. Neither Tijerina nor the Alianza were involved.

Salazar was abducted from in front of his home while opening his gate and was later found murdered in his car. Suspicion immediately turned to Tijerina and the Alianza. The investigation was short lived. Several members of the Alianza were arrested, but all could account for their whereabouts at the time of the murder and no one was charged. A law enforcement official close to the investigation at the time told me some undisclosed Constitutional issue made the case impossible to pursue, though police believe they knew what happened. New Mexico District Judge Joe Angle slapped a gag order on government officials, from the governor on down through law enforcement, to not comment about the case or investigation. Neither Tijerina nor the Alianza were involved. The Albuquerque Journal posted a $7,500 reward. Years later the reward poster still adorned law enforcement office walls.

The Albuquerque Journal posted a $7,500 reward. Years later the reward poster still adorned law enforcement office walls.Tijerina and others were tried in Federal court. The trial venue was changed to Las Cruces in Doña Ana County at the Federal Courthouse before Judge Howard Bratton.

Reies López Tijerina, Cristobal López Tijerina, Jerry Noll, Ezekial Dominguez and Alfonso Chavez were convicted to varying degrees of assault of the two rangers and conversion (stealing) of two forest service trucks. The jury was deadlocked on the conspiracy count on all defendants and the judge ordered a mistrial.

Tijerina was convicted of assaulting the two rangers and acquitted of stealing the forest service trucks. He was sentenced to two years in prison and five years of probation.

Tijerina and Noll were also found to be in contempt of court for having violated a gag order by talking about the case before the trial at an Alianza convention.

Tijerina and Noll were sentenced to 30-days for the contempt.

Tijerina posted a $10,000 bond and was released pending the out come of an appeal.

Tijerina and his fellow defendants appealed the conviction and contempt to United States 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, Colorado, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied Writs of Certiorari rejecting hearing the issues.

The Poor People's March, started as an idea of the late Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Tijerina was chosen by King to be a representative of the Hispanic delegation. His selection was controversial, with some claiming that the Alianza represented land retention and not poor people as typified by southern blacks. However King's vision for the march was not limited to blacks, but was to include all "poor people." He also included, Native Americans, residents of Appalachia, and any other groups deemed poor.

The Poor People's March, started as an idea of the late Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Tijerina was chosen by King to be a representative of the Hispanic delegation. His selection was controversial, with some claiming that the Alianza represented land retention and not poor people as typified by southern blacks. However King's vision for the march was not limited to blacks, but was to include all "poor people." He also included, Native Americans, residents of Appalachia, and any other groups deemed poor.This was the western contingent that started in Los Angeles and worked its way to Washington, D.C.

Marchers passed through Albuquerque, from Dennis Chavez Park to the Old Town Plaza.

Marchers passed through Albuquerque, from Dennis Chavez Park to the Old Town Plaza. Tijerina offers the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference water from a canteen while marching through downtown.

Tijerina offers the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, right, of the Southern Christen Leadership Conference water from a canteen while marching through downtown. Police provided an escort common to such parades and maintained surveillance in the wake of King's April 4, 1968, assassination.