Some can rightly argue that all little boys, at some moment in time, when asked, what do you want to be when you grow up? They would say, “I want to be a fireman.”

It might have been easier in the 1950s and 60s; when a Dalmatian would sit on top of the engine’s hoses barking at a couple of firemen, in what a small kid would describe as their raincoats flapping in the breeze holding on, by wrapping their arm over a highly polished silver bar on the back step.

Firehouses were places of awe and symbols of efficiency. This is the Central Fire Station, built in 1926, in downtown Burlington, Vt., with its red lights beaming to indicate its function and status; all units: Tower 1, and Engine 1, present and ready to respond.

Firehouses were places of awe and symbols of efficiency. This is the Central Fire Station, built in 1926, in downtown Burlington, Vt., with its red lights beaming to indicate its function and status; all units: Tower 1, and Engine 1, present and ready to respond. Helmets and coats neatly lined up, boots, with the pants already attached at the ready next to the truck at New York City Firehouse 8.

Helmets and coats neatly lined up, boots, with the pants already attached at the ready next to the truck at New York City Firehouse 8. It was a time when every fire engine was red and you were more likely to see a pumper in a small town’s Fourth of July parade than at a house fire.

It was a time when every fire engine was red and you were more likely to see a pumper in a small town’s Fourth of July parade than at a house fire.I soon out grew the fireman’s goal, as most kids do; as I grew up my alter ego took up the little boy’s desire. I used it as a joke; still do.

However, I had already given up any desire to be a firefighter when reality struck. In 1970, Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act. The regulations of OSHA took all the fun out almost every dangerous job.

Now firefighters have to sit within an enclosed cab, securely seat-belted in, wearing high-tech aviation-type noise-attenuating intercom headsets.This is Santa Fe's Ladder Truck crew.

Now firefighters have to sit within an enclosed cab, securely seat-belted in, wearing high-tech aviation-type noise-attenuating intercom headsets.This is Santa Fe's Ladder Truck crew.Firefighters are more armored up than ever before with hi-tech fiber protective gear and self contained breathing apparatus, as these Mandan, S.D. firefighters are.

And when was the last time you saw a firefighter swing an ax to crash through a door?

And when was the last time you saw a firefighter swing an ax to crash through a door? It hardly ever happens anymore.

It hardly ever happens anymore.Building codes, better electrical standards, automated fire sprinkler systems in commercial locations, smoke alarms and education have all contributed to fire prevention rather than the need for fire suppression.

This being the ninth anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attack on New York’s World Trade Center, Arlington, Va.’s Pentagon, and the crash of United Airlines Flight 93, in Shanksville, Penn.

This being the ninth anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attack on New York’s World Trade Center, Arlington, Va.’s Pentagon, and the crash of United Airlines Flight 93, in Shanksville, Penn.I thought I might get a jump on the tenth anniversary; so, this is a tribute to firefighters of this nation; full-time, and volunteers, all professionals, if not in pay, at least in attitude.

This is Arlington County’s engine 103, wearing a large Pentagon shaped decal commemorating their participation in responding that fateful day.

This is Arlington County’s engine 103, wearing a large Pentagon shaped decal commemorating their participation in responding that fateful day. This is New York City’s Firehouse 10, which I photographed June 18, 1988, with Ladder 10, a 1984 Seagrave 100-foot aerial truck, responding to a call.

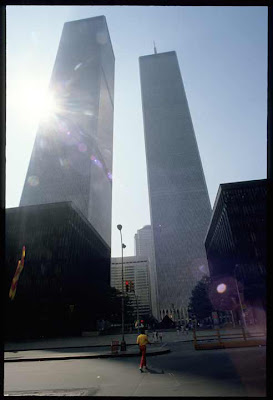

This is New York City’s Firehouse 10, which I photographed June 18, 1988, with Ladder 10, a 1984 Seagrave 100-foot aerial truck, responding to a call. The station is directly across from the South Tower of the World Trade Center at 124 Liberty Street. This view, above, of the WTC was from the driveway of Ten's house.

The station is directly across from the South Tower of the World Trade Center at 124 Liberty Street. This view, above, of the WTC was from the driveway of Ten's house. Ten House lost five firefighters, the station was badly damaged, and both Ladder 10 and Engine 10 were destroyed by the collapsing structures. Here, three firefighters of Engine 10, a 1983 Mack pumper, block traffic to allow the truck to exit its quarters.

Ten House lost five firefighters, the station was badly damaged, and both Ladder 10 and Engine 10 were destroyed by the collapsing structures. Here, three firefighters of Engine 10, a 1983 Mack pumper, block traffic to allow the truck to exit its quarters. Three hundred forty-three members of the NYC Fire Department lost their lives that day.

Three hundred forty-three members of the NYC Fire Department lost their lives that day. I have photographed firefighters as long as I have photographed police officers.

I have photographed firefighters as long as I have photographed police officers.Here is a selection of my work, starting with a 1969 downtown Manhattan Chinese restaurant kitchen fire where the plucked Peking Roast Duck’s feather ended up in the helmet.

Firefighters are unfazed by the presence of a New York businessman, briefcase in hand, or a young photographer watching them work, from behind their trucks.

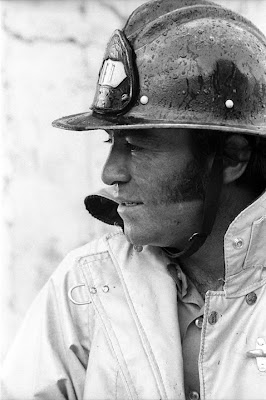

Firefighters are unfazed by the presence of a New York businessman, briefcase in hand, or a young photographer watching them work, from behind their trucks. In my time as an Albuquerque News photographer, I covered several large fires, including this one at Coal and Second street. I worked in and around the firefighters and Fire Chief Ray Khun commended my work and wanted it entered in a firefighters’ magazine photo contest.

In my time as an Albuquerque News photographer, I covered several large fires, including this one at Coal and Second street. I worked in and around the firefighters and Fire Chief Ray Khun commended my work and wanted it entered in a firefighters’ magazine photo contest.

I shot a photo-essay published October 15, 1970, “Day in the Life” of Firefighter J. Baca as he went about his duties.

I shot a photo-essay published October 15, 1970, “Day in the Life” of Firefighter J. Baca as he went about his duties.

I also shot the occasional night fire.

I also shot the occasional night fire.

Fire Departments around the country are proud of their big machines. These photographs were taken in the summer of 2002 during a cross-country road trip.

Fire Departments around the country are proud of their big machines. These photographs were taken in the summer of 2002 during a cross-country road trip. Near Mandan, S.D., along Interstate Highway 94 the local fire department responded to a truck fire that started when a tire went flat.

Near Mandan, S.D., along Interstate Highway 94 the local fire department responded to a truck fire that started when a tire went flat. Being a long way from a fire hydrant, a portable tank was set up and the pumper sucked water at up to a thousand gallons a minute.

Being a long way from a fire hydrant, a portable tank was set up and the pumper sucked water at up to a thousand gallons a minute. This is Denver’s Engine 8, sporting the “Top Run” designation as the busiest unit in the department.

This is Denver’s Engine 8, sporting the “Top Run” designation as the busiest unit in the department.

The officers were out conducting a fire safety inspection.

The officers were out conducting a fire safety inspection. The South Burlington, Vt. fire and rescue sits as its crew checks a medical emergency at a shopping mall.

The South Burlington, Vt. fire and rescue sits as its crew checks a medical emergency at a shopping mall. So what’s wrong with this picture?

So what’s wrong with this picture? Just before 8:00 PM on June 23, I observed smoke billowing and blotting out the sun; there was a three-alarm warehouse structure fire at Rosemont along Broadway Boulevard, N.E. in the Springer Industrial Center. The situation was compounded by high winds of 31 mph, with peak gust speeds of 39 mph.

Just before 8:00 PM on June 23, I observed smoke billowing and blotting out the sun; there was a three-alarm warehouse structure fire at Rosemont along Broadway Boulevard, N.E. in the Springer Industrial Center. The situation was compounded by high winds of 31 mph, with peak gust speeds of 39 mph. Here’s the little kid, about the right age to think, he’d like to be a fireman when he grows up, with a front row seat.

Here’s the little kid, about the right age to think, he’d like to be a fireman when he grows up, with a front row seat. The location was the most controlled outside scene I have ever seen, fire or criminal. The reason for such control was the geography and the structural barrier, a wrought iron fence.

The location was the most controlled outside scene I have ever seen, fire or criminal. The reason for such control was the geography and the structural barrier, a wrought iron fence. Fire and police units were able to secure Broadway between Mountain and Odelia with only a few units.

Fire and police units were able to secure Broadway between Mountain and Odelia with only a few units. The east side of the street was also a block long warehouse.

The east side of the street was also a block long warehouse. Only a couple of strips of yellow "crime scene" tape were necessary to contain spectators.

Only a couple of strips of yellow "crime scene" tape were necessary to contain spectators. Though there was a lot of smoke there was little to no visible flame.

Though there was a lot of smoke there was little to no visible flame. The fire seemed to be concentrated in TMM Business Records Storage and Management, which had about 150,000 boxes of business records fueling the fire.

The fire seemed to be concentrated in TMM Business Records Storage and Management, which had about 150,000 boxes of business records fueling the fire. There were 73 fire personnel on scene and 23 fire units ringed the building.

There were 73 fire personnel on scene and 23 fire units ringed the building. Several rescue squads were on scene, but had little to do, because no firefighters entered the building.

Several rescue squads were on scene, but had little to do, because no firefighters entered the building. Engine three from Girard at Central Avenue N.E. was set up outside the fence on Broadway and was redeployed. The crew rolled up its five-inch large diameter fire hose that was attached to a fireplug and went behind the building.

Engine three from Girard at Central Avenue N.E. was set up outside the fence on Broadway and was redeployed. The crew rolled up its five-inch large diameter fire hose that was attached to a fireplug and went behind the building. Battalion chiefs and other ranking officers, Fire Chief James Breen, driving and Deputy Chief Richard Sears monitored the situation.

Battalion chiefs and other ranking officers, Fire Chief James Breen, driving and Deputy Chief Richard Sears monitored the situation. KOB TV Eyewitness News’ Kayla Anderson got an interview with mid-level supervisor.

KOB TV Eyewitness News’ Kayla Anderson got an interview with mid-level supervisor.

About an hour after the start of the fire this APD Officer approached and said, “You are ordered to the corner of Broadway and Odelia, where the Mayor and Fire Chief will brief the press.”

About an hour after the start of the fire this APD Officer approached and said, “You are ordered to the corner of Broadway and Odelia, where the Mayor and Fire Chief will brief the press.”I asked who sent the order? The young officer said, his lieutenant.

I indicated I had no need to cover either the Fire Chief or Mayor. The officer then ordered me and all the citizens who were watching, about a half-block east of Broadway to a point where the firefighting activity could no longer be seen.

It seemed to me, little has changed since the Officer Daniel Guzman attack on then KOB TV’s Chief Photographer Rick Foley. Guzman ordered Foley to a distant intersection where there was an incident command center in an effort to round up and corral the press away from the actual scene where a suspect and two others had fled from a traffic stop. One suspect was later determined to be wanted for murder and had exchanged shots with officers. He hid in a dumpster, was eventually shot, more than once, and then arrested.

The attitude resulting in this order violates the department’s On-Lookers policy, section 1-31 of APD's General Orders, which allows citizens to watch police and other city workers perform their jobs, and specifically: to photograph, video, and audio record events.

1 comment:

you made it lengthy but it was an interesting read. I hope you will be there at what you are aiming and all the best.

Los Angeles Traffic School

Post a Comment