It is a wreck. This Mercedes Benz transport turned over along Kenya’s highway A109 from the capital, Nairobi to the country’s major Indian Ocean port city of Mombasa. These pictures were taken 10 years ago. It represents the political reality that country was and still is experiencing. I doubt much has changed in the rural parts of the country.

It is a wreck. This Mercedes Benz transport turned over along Kenya’s highway A109 from the capital, Nairobi to the country’s major Indian Ocean port city of Mombasa. These pictures were taken 10 years ago. It represents the political reality that country was and still is experiencing. I doubt much has changed in the rural parts of the country.The Republic of Kenya acquired its independence from the United Kingdom’s Empire when it was British East Africa, in 1963. It is considered one of the most stable democracies on the African continent. It uses the British common law and its own statutes as its legal basis. Kenya has a population of about 37 million and is about the size of the state of Nevada.

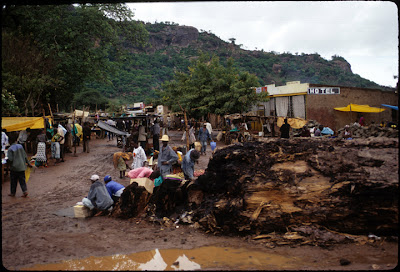

I was on a cruise with my parents and Mombasa was the original destination for the Kenyan leg of our trip. However, the British government had posted a travel advisory about its former colony, based on political instability in Mombasa.

In 1997, the country was preparing for national elections and it seemed that the local political party around Mombasa was taking to the streets, protesting their allotment in the country’s National Assembly known as the Bunge. The British advisory, like those of the United States and the European Union, are usually considered very seriously by each other and followed. In this case, port activity dropped to a minimum, dockworkers had little work, the local economy suffered and the trade route traffic was reduced to a trickle. A short while later, the local political party, feeling economic pressure, announced that it had reevaluated its claim and agreed that the election commission’s apportionment was accurate. The local thinking at the time was that the economics of the boycott was hurting the political party’s chances in the upcoming elections.

About half the population lives in poverty. Seventy-five percent of those working do so in agricultural endeavors, yet only eight percent of the land is arable, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s World Fact Book. Over the past five years, anti-corruption efforts and reform measures have waned.

About half the population lives in poverty. Seventy-five percent of those working do so in agricultural endeavors, yet only eight percent of the land is arable, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s World Fact Book. Over the past five years, anti-corruption efforts and reform measures have waned. President Mwai Kibaki, a member of the Kikuyu tribe, the largest in the nation, ran for reelection to a second five-year term. He was narrowly elected Dec. 27, 2007. Immediate disputes over the validity of the election process were raised. International and independent poll watchers have refused to verify the outcome. The United States and European Union will not recognize the election results. The African Union and the Commonwealth observer mission are attempting to mediate.

Chairman Samuel Kivuitu of Kenya's electoral commission has indicated that pressure from the ruling party to quickly declare Kibaki the winner was applied, while he acknowledged that there were inaccuracies in the results.

Kibaki has already been sworn in and violence has broken out across the country killing over 300 people. Over 100,000 people have been displaced.

The road to Mombasa, that was patrolled by traffic officers, like this stationary patrol, is now closed. The ruling government refuses to accept any outside efforts for assistance and has sent police to quell the violence.

The road to Mombasa, that was patrolled by traffic officers, like this stationary patrol, is now closed. The ruling government refuses to accept any outside efforts for assistance and has sent police to quell the violence. Kibaki has agreed to talk to the opposition, but only if calm is restored. All governments that face internal violence must take that stance. However, if the violence persists, the chances of peaceful resolution are highly unlikely.

Now, the election might well have been fair, properly run and above board. Any perception otherwise would be put to rest by acceptance of the ruling party to a thorough audit of the votes. There may be problems as some ballots may have been prematurely destroyed.

The political divide initially appeared to be along economical lines -- poor versus rich. Ethnic and tribal clashes seem to have now escalated as the level of dissatisfaction grows.

The political divide initially appeared to be along economical lines -- poor versus rich. Ethnic and tribal clashes seem to have now escalated as the level of dissatisfaction grows.  The economics of Kenya may be influenced, as demonstrated by the placement, order and size of the flags that flew in front of the Nairobi Hilton Hotel. From left: the United Kingdom, the United States, Kenya and the European Union.

The economics of Kenya may be influenced, as demonstrated by the placement, order and size of the flags that flew in front of the Nairobi Hilton Hotel. From left: the United Kingdom, the United States, Kenya and the European Union. So what’s wrong with this picture?

This young man pointed at me as we drove slowly by the crash site. Our driver, James, a retired Kenyan army solider, warned me that some citizens did not like the presence of foreign tourists and might throw rocks at his tour van. Apparently, tourism didn’t impact the youth economically, as it did others.

This young man pointed at me as we drove slowly by the crash site. Our driver, James, a retired Kenyan army solider, warned me that some citizens did not like the presence of foreign tourists and might throw rocks at his tour van. Apparently, tourism didn’t impact the youth economically, as it did others. “Power comes from the end of a gun,” Mao Tse Tung, chairman of the Chinese Communist party and Dictator of the People's Republic of China said. Mao was not the most democratic thinker in the world. However, his quote may have some real truth to it.

This past week, Kenya was not the only democracy where violent incidents may disrupt what is called the democratic process of “free elections.”

Former two-time Pakistani Prime Minister Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto was assassinated Dec. 27 at the end of a political rally, by a man who fired between three and five rounds before detonating a bomb, killing 35 people.

The event took place in Rawalpindi, eight miles south of the capital, Islamabad. Rawalpindi is the home of the military headquarters and the site where her father, the former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was hanged in 1979, after being deposed in a military coup.

Bhutto returned to Pakistan on Oct. 18, to run for office in the scheduled Jan. 8 elections. She was under death threats and while traveling from the Karach airport into the city, two bombs were exploded killing about 200 people.

Had Bhutto been elected and her Pakistan People's Party prevailed, it was almost certain that she would again become Prime Minister. Her two previous stints as prime minister ended with charges of alleged corruption and she went into self-imposed exile in Dubai.

President Pervez Musharraf had earlier declared a state of emergency and imposed martial law upon the country. It was just before the supreme court, whose justices he had appointed, were about to hand down an opinion that would have required Musharraf to give up his role as head of the military to run for president. Ironically, Musharraf gave up his general’s uniform shortly after restoring freedoms. He did not restore the supreme court justices to their positions.

Pakistan is a vital ally to the U.S. and holds an important role in fighting terrorism. It also poses potential threat as a nuclear power. It is one of the few democracies from the Middle East across the Asian continent, though it borders the largest democracy in the world, India. They are no friends as they have always had differences over land disputes and religion.

The democratic process in Kenya and Pakistan is clearly stressed.

So, what does this have to do with our democracy?

This week, the election process in our country takes its first formal steps with the Iowa caucus and then the New Hampshire primary. They will, in all likelihood, eliminate many if not most of the candidates in both parties.

As messy as our politics are, our history has had its share of violence.

In 1968, the assassination of Robert Kennedy during the primary season resulted in Hubert Humphery, left, becoming the Democratic Party’s candidate against Republican Richard Nixon, right.

In 1968, the assassination of Robert Kennedy during the primary season resulted in Hubert Humphery, left, becoming the Democratic Party’s candidate against Republican Richard Nixon, right.  In 1972, Democratic Party nomination hopeful, Alabama Gov. George Wallace was the victim of a would-be assassin in a Laurel, Md., shopping center. He is seen here, sitting in a wheelchair, at the top of the podium, behind President Richard Nixon, during his second inaguration, Jan. 20, 1973.

In 1972, Democratic Party nomination hopeful, Alabama Gov. George Wallace was the victim of a would-be assassin in a Laurel, Md., shopping center. He is seen here, sitting in a wheelchair, at the top of the podium, behind President Richard Nixon, during his second inaguration, Jan. 20, 1973.It is doubtful that our election process will not be an orderly affair. There is a fair amount of criticism about how the relatively small state populations of Iowa and New Hampshire are likely to determine the candidates for the general election. It is the nature of the process that allows for quick and almost certain lethal blows to be administered to candidates’ campaigns that do not charm the early primary voters. The political pollsters will argue that if you can’t energize the cold weather voters, you’re not going to do any better in the other, later primaries.

What is happening in the world is evidence of how fragile democracies also can be.

No comments:

Post a Comment